Introduction to the Game

Spacefolk City is an approachable, quirky and absurd take on the city-building genre, built from the ground up for VR platforms. Players collaborate together with bizarre Spacefolk inhabitants to construct a little floating city in space. You must keep them happy and productive, and eventually help them find a way to escape the impending catastrophe of their sun going supernova.

Unlike traditional flat-surface city builders, Spacefolk City cities are floating clumps of buildings which Spacefolk walk on. The mechanics of the game encourage players to build creatively in 3-dimensions, with houses and buildings placeable at odd orientations. Compared to traditional city builders there is also greater focus placed on individual Spacefolk citizens, so cities tend to be much smaller and more compact in scale.

Together with my collaborator Vincent Diamante, we created a soundtrack of 22 songs for the in-game radio station “Spacefolk FM”. We also produced the Spacefolk language, and a distinctive bed of real and synthesized sound effects. This was all assembled and implemented in Audiokinetic's Wwise.

Music First

At Moon Mode I’m privileged to work with a team who truly understand the importance of music, and the emotional impact it can have on the overall game experience. For us, discussions about musical aesthetics always commence right at the outset of the entire project, and we are committed to always working in this way.

This is preaching to the choir, but there are so many benefits of incorporating audio design, and specifically music design, right at the outset of the concept art phase. A healthy collaboration between music production and concept artists can set a rich, detailed, and intuitive “creative compass”, allowing for a seamless integration between sound, art and gameplay. This will always be a better option than leaving music until the later stages of production, when it’s too late for audio to impart any influence over the game’s design.

In addition, having collaborators with a sophisticated and diverse appreciation for music is also extremely helpful. Our chief artist and creative director Therése Pierrau and I have worked together for almost 8 years now, and our conversations about music are always enjoyable. She has a broad understanding of music, if from a purely emotional perspective. Her reactions to music often serve as a stark reminder to not let any of the technical aspects of music choice distract me from how music emotionally affects the listener.

There was one important technical consideration to think about though: the music choice would have to be something easily mixable for a satisfying sound on the small built-in speakers of an Oculus Quest. Although the Quest has a headphones jack, the internal speakers are extremely convenient and are a key part of its cordless, tetherless appeal. Our music would have to sound like it was a good, natural fit for these small speakers.

Aesthetic Direction

Visually, the objective was to create a world that was fun, vibrant, full of diversity, and just a bit silly. The main protagonists were to be absurd things like pizza slices, hotdogs, lemons, books, sand buckets, etc. Therefore, it made sense that we needed something a bit bizarre, but still recognisable in the same way that a pizza-headed spaceling would be (!). A funky “sci-fi B-movie” feel would also help to complement the setting.

We decided that the late '70s and early '80s would be a good place to start. That era saw such an interesting collision between the worlds of jazz fusion, prog rock, disco, and the advent of affordable synthesizer technology, all sowing the seeds for house music and new wave to follow. The specific album which I recommended to Therése was 1979’s “Solid State Survivor” from the Japanese electronica band Yellow Magic Orchestra. This seemed to represent the best encapsulation of the criteria we had defined, and Therése immediately approved of its eccentric tone, campy futurism, and sense of humour.

This era of music also addressed the technical consideration of small speaker reproduction. With the rise of portable music on FM transistor radios and the Sony Walkman in 1979, mixes of the time were beginning to favour a sound that would work equally well on small speakers. That tight, close-mic'd, scooped sound would be perfect for satisfying reproduction on the Oculus Quest.

Music Production

With that set as a guideline, I got in touch with an old colleague of mine from game audio circles, Vincent Diamante. Vince has an extensive knowledge of early Japanese pop and the influence it had on the development of video game music, so I knew he would intrinsically understand this direction. As expected, he was intimately familiar with Solid State Survivor, so we agreed on that as the general guideline for our soundtrack. We would use this album as a start point, but also allow the game aesthetics to pull us freely in various directions as the art style matured.

Fast-forward to the end of the soundtrack production process, and we had 22 songs created between us. Unsurprisingly, we found ourselves somewhat distant from Solid State Survivor: we had some acid techno, Italo disco, jazz fusion and a few rather ridiculous parodies of other styles from the era, none of which were particularly evocative of Yellow Magic Orchestra. But that was OK; in the context of the game’s absurdity and eccentric look, this degree of diversity was a good fit.

Radio Playback System

Besides the music itself, Vince was particularly interested in getting the feel of an FM radio station and not just a set of cool tunes. After some discussion involving the radio station name (some early favourites include Radio Gamma-Ray, and Lightspeed Radio: “Radio… at the speed of sound!”), we finally settled on Spacefolk FM. Vince got to work on tracking some short, under 15 second musical stingers, as well as recording himself as a hyped-up radio DJ announcing the radio station (“Setting your ears on fire… with Spacefolk FM!”)

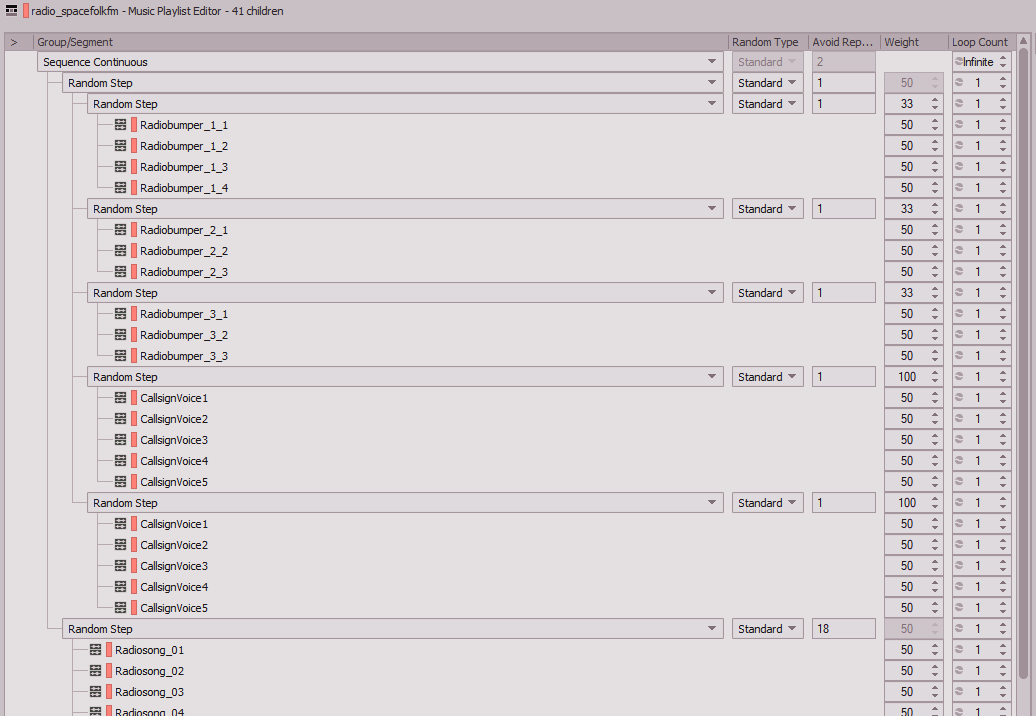

With a collection of both plain DJ VO-only station IDs as well as fleshed out music+VO bumpers, it became clear that structuring the delivery of the radio station the right way would go a long way towards immersing the player in the FM radio feeling. The obvious stuff was quick to set up: a big music playlist sequence that would continuously play, alternating between program material (music) and callsign announcements. On a real radio station, however, callsign announcements could be had not only in different permutations (with or without music), but also in different places, often overlapping with the beginning or end of the musical program material, acknowledging the coming or already past track change. This led to the simple but not-so-obvious solution: creative use of exit cues to encourage dovetailing of music tracks and bumpers.

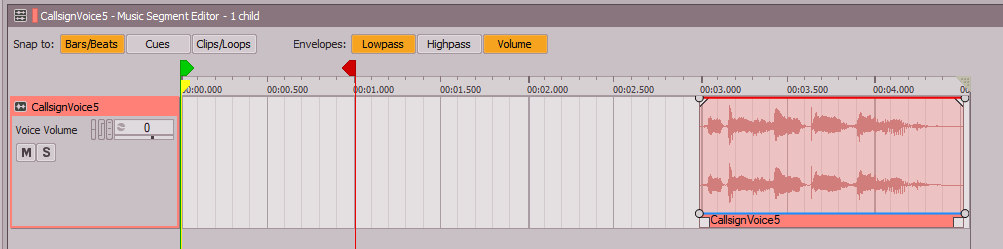

(Shown: Voice only callsign with red exit cue occurring 2 seconds before voice is actually heard)

When one of the music tracks approaches (but not quite reaches) the end of the song, it will already hit an exit cue in the middle of the fade out, at which point it will go to the next track in the radio playlist. Maybe it will be a full music+voice identifying bumper, but it could also be a voice only music segment. As you can see above, the voice actually doesn’t occur until well after the exit cue… which means that the playlist will already have triggered the next music track (guaranteed to be a song from the program material) and been playing for a few seconds before you hear the DJ identify the radio station. This variation in the timing of the callsign in addition to the variety of the recordings really helps in selling the feel of the FM radio station.

The Loudness Button

A nostalgic feature of playback systems of the era was the ubiquitous “Loudness” button. As a child I remember always finding it rather amusing that switching the Loudness button on would result in such a significant “improvement” to the sound, with all that added bass and treble. I would wonder why the HiFi would even need a button for this; why not just leave it on all the time? Who would possibly prefer the boxy, thin sound of playback with Loudness off? (The innocence of youth!)

So: our in-game radio would definitely need a Loudness button that was designed to be on all the time. If you turned it off, it would drastically reduce the sound to the scale of a little transistor radio speaker, so you’d also question “What is this even for?”

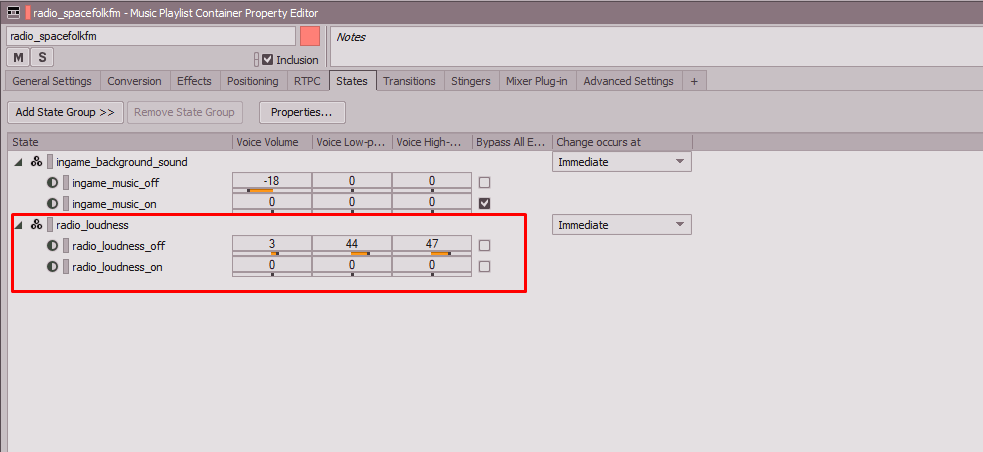

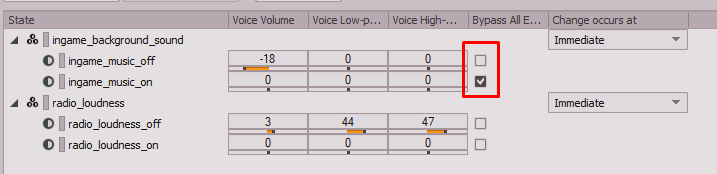

There are several easy ways to achieve this in Wwise, but I elected to simply tie some activation/deactivation events to a State change on the master container for the radio elements:

Critical functionality complete!

The Sound of Space

Finally, we needed to address the dreaded possibility that the player might want to actually turn our wonderful soundtrack off.

After some fun conversations with Vince about the irony of “the sound of space”, we concluded that space indeed needed some kind of ambience, and that it should feel slightly dark and heavy for contrast. I decided to start with an ambience loop that would consist of two components: filtered pink noise, and a very subtle oscillating sine sweep.

For the pink noise, I ensured that there was a good deal of bass content in the side channels. On headphones this would give a heavy out-of-phase effect, adding extra weight and sonic pressure. I did experiment with having the noise actually out-of-phase for a really intensely uncomfortable weight, but opted against this in case it might contribute to simulation sickness or VR nausea. Probably unlikely, but user comfort is top priority for Moon Mode’s productions, so I decided against this.

The sine sweep was actually inspired by the interior ambience sounds from the Death Star in Star Wars: A New Hope. If you listen carefully during the quieter scenes on the Death Star, you’ll hear a sine wave slowly oscillating up and down in the background, like an artificial representation of wind resonating through the structure. I always thought this was a brilliantly simple way to add dynamic movement to an otherwise static artificial ambience bed.

While connecting the ambience to the power button on the radio, another idea occurred to me. Being a radio station, you would expect that switching off the power wouldn’t pause playback, but rather just mute it. This way when you switch the radio back on, the broadcast will have advanced. Instead of simply muting though, what about if the music remained audible but was drastically distanced, as if the radio waves were faintly audible through the vacuum of space (of course, how scientific).

To achieve this, I set up a 100% wet Wwise RoomVerb on the radio container. When the radio is switched on, a State setting would bypass this so that the music is heard directly. However, when switched off, this reverb would be heard at full wetness to give the impression that the music was somehow faintly audible very far away in the expanses of space. The effect is extremely subtle and I doubt most (if any!) players have actually noticed this, but it was a fun little feature which hopefully adds a nice discovery moment for attentive players.

Here is a demonstration of the radio’s loudness feature, as well as the sound of space:

Conclusion

If you would like to hear the final soundtrack, it is now accessible on streaming platforms! Enjoy!

SoundCloud

BandCamp

Other links to streaming platforms, the trailer video, and the game itself are accessible via our LinkTree!

If you're interested in finding out a bit about the sound effects implementation of Spacefolk City, I was recently invited to appear on Wwise Up On Air together with Vince to discuss our work with Damian Kastbauer! Check that out here!

댓글