The preservation of sound in the video game industry is a delicate matter. Whether you are a demoscene and retro enthusiast, or a sound professional working with today’s tools and engines (or both: a modern game music composer with high interest in old sound), chances are good that you have come across questions and problems that are similar to the ones we will review here. I am going to explore what it really means to “archive” sounds because there are a lot of misconceptions about what archiving is and its purpose. In this first article we will start with a quick overview of some basic elements before approaching more concrete and interesting examples in the next part of this series.

Why do we need to keep track of things, and how?

Archives are usually imagined in a dark room or a desk drawer full of very old, lost treasures. In general, archives are also seen as an open chest that anybody could ransack for their personal interest. The activity of archiving in the videogame industry is easily seen as some kind of pirate or hacker’s activity. The recent fever regarding the massive data leaks (including historical, technical, but also employees’ and financial data) stolen at Nintendo and Capcom, led some people to deem the work of hackers necessary. This is a perfect example of a very common misconception about archiving in the field. The status of abandonwares is commonly quite complex, as they may or may not be claimed by their legal owners. This has challenged some genuine archivistic work which aims to preserve games nobody seemed to care about anymore. All of these statements hold some truth, but the reality is that most of the archives are at the complete opposite of these definitions, and for a lot of good reasons.

Why do we need archiving? Historical documentation and cultural highlighting are the most common reasons. However, as companies are aware, good archival practices are far more “interesting” than that. Another reason archives are important is that traces of ongoing business practices and documentation will be relevant for current and future business activities. This is what is called records management, and it affects all of us. There is no contract if you (or your employer) can’t find it anymore, no publishing or patenting rights if no-one is able to locate the papers. There would be no book or music distribution if we no longer have the texts and recordings. Keeping track of things is the best way to ensure they are safe and far from intrusive eyes and ears. Speaking of records being kept safe; describing who can access what, from where, when and for which reason is another one of the numerous missions of the records manager. Missions that have become critical nowadays, with distant access and remote working.

One last role archiving plays that I’d like to highlight in this rapid overview, and probably the most underestimated advantage is the one we will focus the most on is helping today’s work with yesterday’s knowledge. This may seem like it might only apply to some obscure R&D branch in a scientific environment, but it is actually extremely important, pretty much everywhere, and for everyone. Since retro-gaming has become popular in the videogame industry, remasters, remakes, along with emulated ports being made officially; gathering, understanding and recycling ancient data has become a hot topic.

Sound Shape and Soundscapes: Why is it so difficult to archive sound?

If you have some interest in game and sound archiving, there is a high probability that you have already heard of some dreadful stories about archiving and loss. From games and game soundtracks being removed from stores for technical or copyright reasons, to remasters and ports that have gone wrong because of major incompatibilities between two consoles or an “oh shoot, nothing works, we need to recreate the whole sound spatialization and filtering system from scratch in one week!”. The culprits for sound loss are numerous and most of the time the question is not about how well the work has been kept, but rather in what format it was kept.

A game sound archive can be a lot of things, the most obvious form is audio-related, like soundtracks (whether they are on CDs, as files on a desktop, or in streaming services). When it comes to the composer, sound archives are a little more specific. They can be original files that come out of their digital audio workstation, like a WAVE, Vorbis, MP3 files, or any other uncompressed or compressed format. However if we go back even earlier in the process of creating music, sound (and soundtracks for games), archives can be MIDI files, soundbanks, sound cards, synthesizers, software and plug-ins, or even good old fashioned scores written for recording sessions.

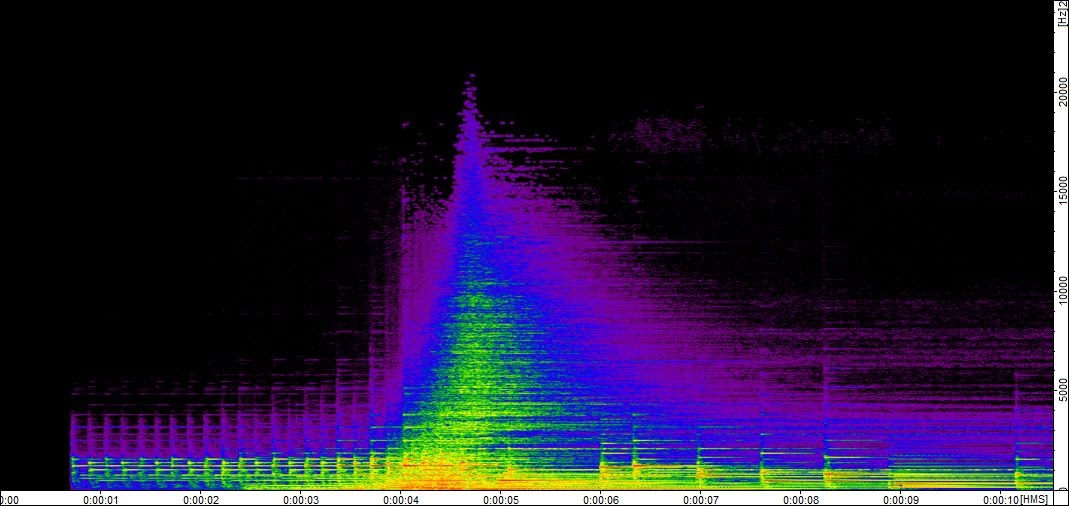

The archiving of sound is by definition quite complicated, because sound’s physical properties cannot be captured and reproduced easily. If a painting will always be a graphical representation of something that is easy to understand with one look, a CD, a score or even a musical instrument will require some kind of technical interaction and knowledge before revealing what they are all about. Just like games, sounds need to be played to be remembered, and from this point of view, they share similar issues as they are ephemeral arts, bound to complex technical and technological objects, senses and feelings. Not all formats are viable for proper archiving because they are not stable enough. They or the software reading them will evolve through time, making older files either sound different or be impossible to read. The same files can get corrupted, equipment can break and functional spare parts become more and more difficult to hunt down as they get older. Whether you like to make sound by using a GameBoy, a PC-88 or a Yamaha DX7, you may know that emulation is rarely as precise or accurate as you would like it to be. And that we can easily transcend a lot of technical difficulties (hence forgetting them) if we don’t have the real gears in our hands at some point.

Furthermore, sound in games has an additional layer when it comes to archiving: preserving music and sound effects as independent assets is a first step. But in order for them to be reachable from an historical or even a professional perspective, we need to archive how they are working within the games they are included in for multiple reasons. If the creation process is an eternal loop of trials and errors, sound in the final product often escapes the control of the creators. Beyond procedural music (which is a whole world by itself), games rely on multiple layers of dynamic music, on stems, live filters and so on, who evolve depending on the player’s actions, or even on the game’s environment itself. In some cases, sound in games ends up being very different from what a composer hears in their workspace. Inevitably, sound is bound to a game’s engine and layers of code that can’t be ignored to fully understand what was going on during creation.

When digging into game sound history to analyze old soundtracks, the question that arises without fail is “Why?”. Why are the files organized this way? Why is this ripped-off MP3 sounding weird outside of the game? What did the composers have in mind when writing this? What challenges did they face that lead to the final result? Most often answers aren’t given when you ask those involved for their stories. In the end these stories become somewhat of an interpretation containing some truth without ever really knowing what went into the work. This could be your work one day. The work of the present day composer, sound designer, game audio programmer, your work and process could also be lost one day. The current tips and tricks professionals know by heart today could be completely lost in less than ten years. In part two of this series, we will go over a post-mortem from a research project that was supposed to be very simple, but ended up with a mystery and questions that we had trouble answering. Stay tuned to learn about how we almost rewrote the history of an MP3 in Conker’s Bad Fur Day (Rare, 2001) with complete nonsense because we lacked one essential piece of information.

.png)

Commentaires