Production quality in video games has been steadily evolving over the past few decades, and this is true of the audio portion as well. This, in no small part, is due to advancements in tools and techniques. In this article, we'll look at what sets apart game audio from more traditional mediums, what the current state of the art is in terms of workflow, and how this relates to audio in the new realities, interactive or otherwise.

The linear audio production workflow

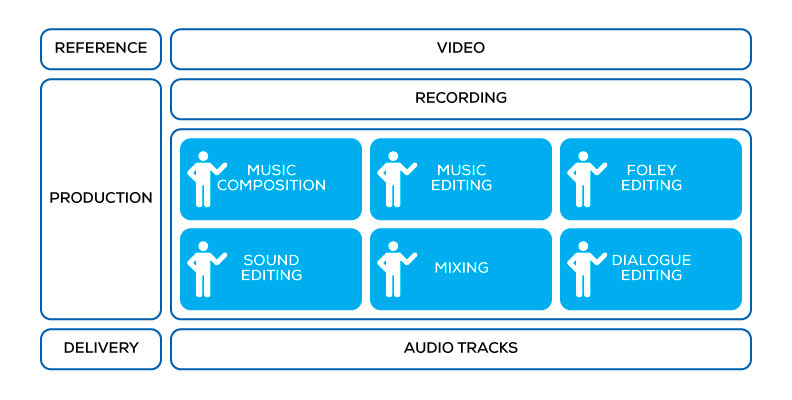

First, let's look at how audio content is produced in the case of linear experiences, such as film and television. Artists work based on a video reference and produce a corresponding audio track. Several crafts are involved in this: music composition, music editing, foley editing, sound editing, dialogue editing, and mixing. Artists, experts in these respective fields, have the luxury to be able to do this using a tool called the Digital Audio Workstation. Layers upon layers of the finest ingredients, crafted, tuned, and mixed by expert hands, are arranged to match video perfectly, supporting and enhancing the overall experience.

Linear audio production

Linear audio production

In the ideal case, we can say that artists can create the audio content based on a perfect reference—the visual component of the experience exactly as shown to the audience—and have complete control over the final experience: what they export from the DAW is exactly what will be played back.

Linear playback. 35mm film containing synchronized sound and pictures. Lauste system circa 1912.

Linear playback. 35mm film containing synchronized sound and pictures. Lauste system circa 1912.

The interactive audio production workflow

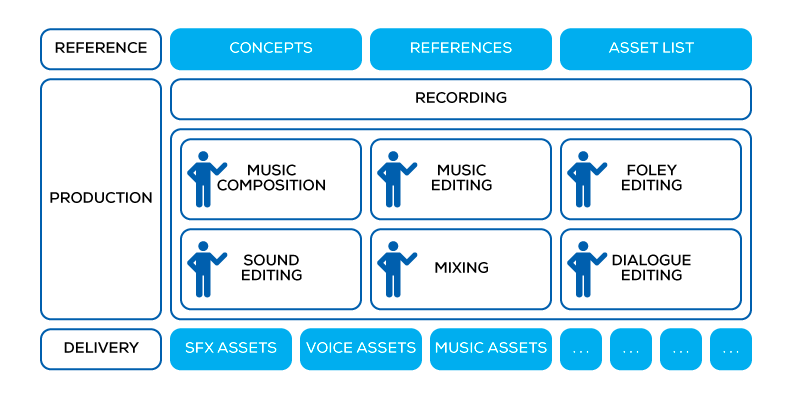

Moving on to interactive audio production, a fundamental change happens: there is no complete, linear piece of video to use as a reference. Games are interactive, and interactivity means that the timeline of events is not predetermined, emerging instead from the player's actions. So, instead of a linear reference, there will be ideas, concepts, bits of animation: fragments of the experience which will be combined together when the game is played.

What the audio department needs to produce is individual audio assets: individual WAV files exported from a DAW.

Game audio production

Game audio production

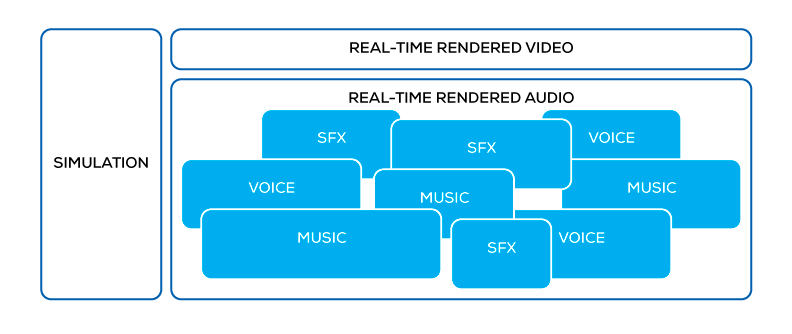

The game team integrates the audio assets in the game, the game's engine drives playback according to spatial audio rules and parameters defined in code or in the game editor.

Game audio playback

Game audio playback

Too often, this is where audio artists' involvement in the process gets reduced or even eliminated. They will have created assets out-of-context from the final experience. All of the aspects of the soundscape suffer; most obviously, the mix can be completely unbalanced, and music relegated to being just 'background music' instead of a real storytelling element.

The game audio production workflow—with dedicated tools

“Implementation is half of the creative process.” – Mark Kilborn (Call of Duty)

The need for artists to be involved in the implementation phase, so that they are able to define how audio should react based on the playback context, emerged with game audio, creating the demand for dedicated interactive audio production tools. Game audio pioneers found very little in terms of available software tools that could be used for this purpose. Audio programming environments, such as Max/MSP and Supercollider, offer the necessary programmability, but are very unfamiliar territory when coming from DAWs and are not oriented for productivity at the scale of game asset production.

This is how game audio middleware was born. From the early days of direct programmer involvement in the sound design, best practices were extracted and artist-friendly toolsets were built around them.

Game audio middleware is an additional step in audio production, between the DAW and the game editor. The idea is to use the DAW to handle the purely linear aspects of audio, and then move to another authoring environment where an artist can produce complete, intelligent audio structures: the combination of assets and behaviors.

Explaining all the features that it contains is beyond the scope of this article, so let us focus on the interactive music toolset to get a glimpse at what building an interactive audio structure entails.

Interactive Music Toolset

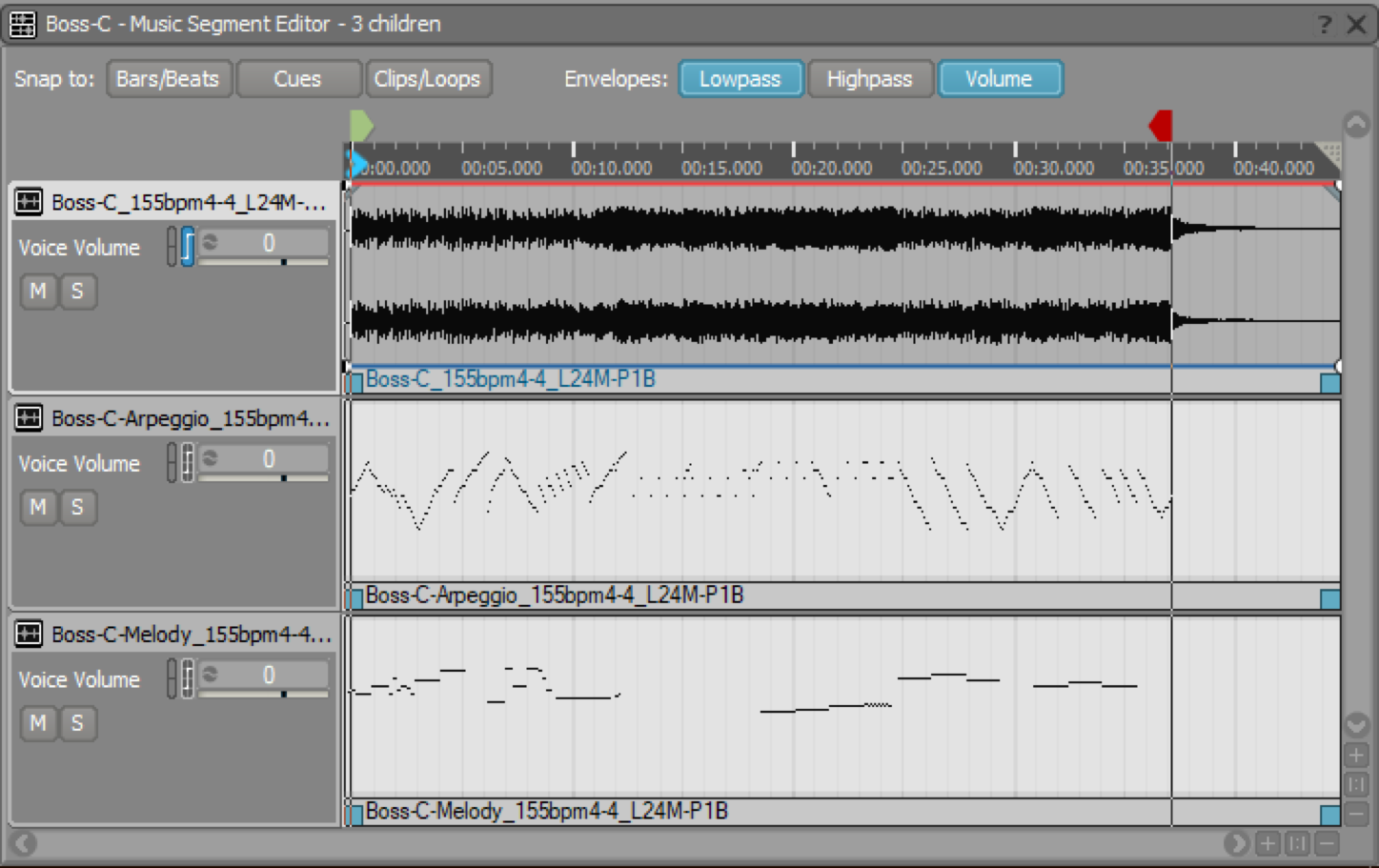

Individual segments from tracks are exported from the DAW and imported as clips on tracks in the Wwise Interactive Music Hierarchy.

Wwise music segment editor

Wwise music segment editor

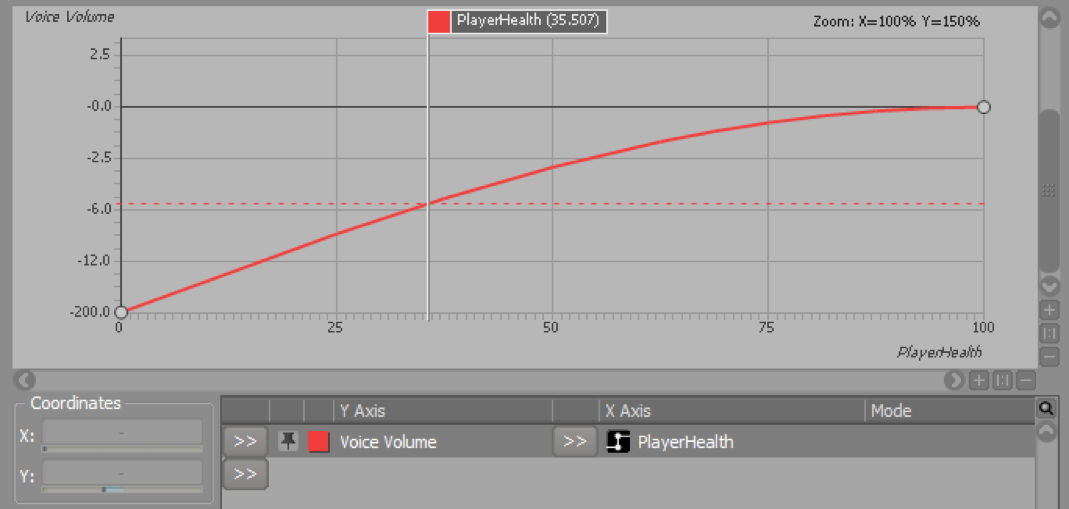

Game parameters can be bound to mixing levels,

Wwise game parameter graph view

Wwise game parameter graph view

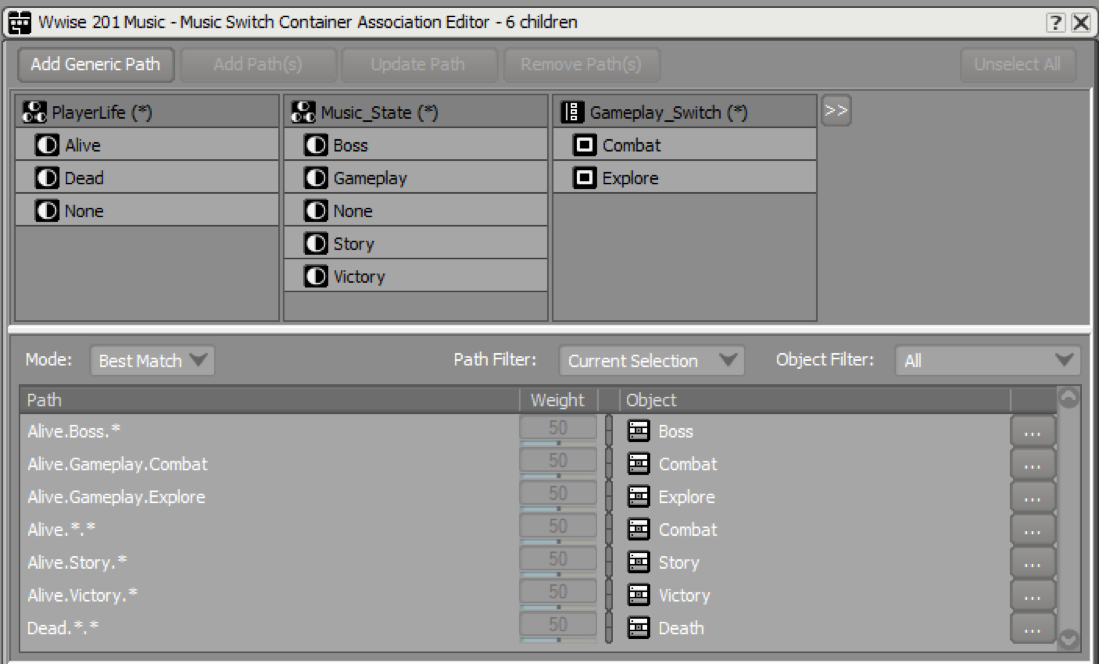

game states can be bound to music segment selection as part of a music switch container,

Wwise music switch association editor

and specific gameplay elements can trigger musical overlays called Stingers. Finer segmentation allows for a more interactive structure and a more accurate response to the behavior of the game simulation.

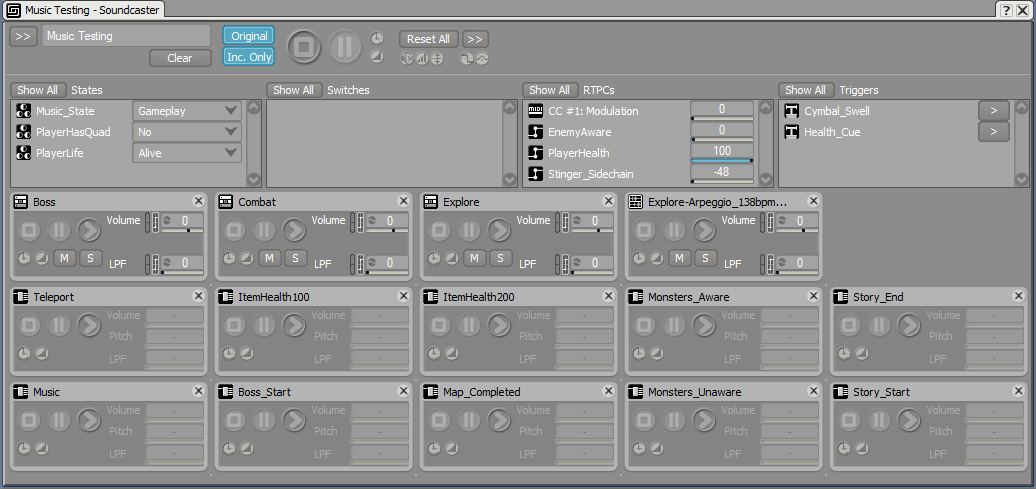

Iteration is the key to achieving perfection. In the same way that a DAW allows a composer to quickly make adjustments to his musical composition and instantly hear the result, an interactive music composer needs to be able to adjust the game bindings until the desired behavior is achieved. Wwise offers both the ability to manually simulate game stimuli,

Wwise Soundcaster

and the ability to connect to an actual running game, inspecting how the structures react and making changes on-the-fly.

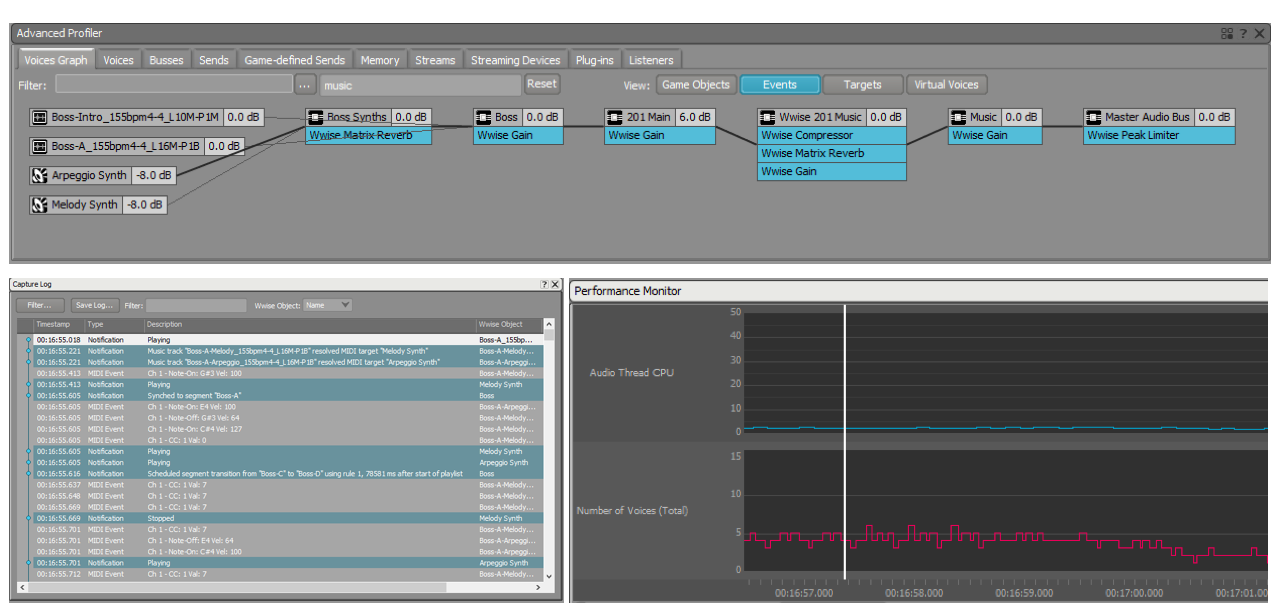

Wwise interactive music profiler

Wwise interactive music profiler

Application to VR storytelling

There is no question in our minds that all of this directly applies to VR games, but what about the more linear, storytelling-like experiences? Of course! To illustrate this, let's explore the most linear category of experiences: 360 videos.

The shift from regular video to 360 introduces one degree of freedom for the viewer: viewpoint rotation. As the viewer's head rotates, the view in the display shifts to correspond to the new perspective and, at the very least, it is completely natural for the audio to react in the same way. This has become the baseline standard for 360 AV content, with ambisonic soundfields being the audio sphere complementing the video.

We can go one step further and acknowledge that some part of the audio is not actually part of the world (non-diegetic) and, therefore, should not be spatialized but simply played back as a stereo stream straight to the headphones. Additionally, it is possible to implement a sort of 'listener cone' so that what is currently in front of the viewer stands out in the mix. An example of this is the focus effects in the FB360 spatial audio workstation.

Such a pure binding between rotation and spatialization is the realistic and accurate thing to have (although the introduction of focus is not), but it does not leave much room for artistic direction! In traditional video, the sound department will often steer well clear of realism in order to convey the right impression and extract the right emotions from the audience. As with games, artist-defined playback-time behavior needs to be introduced.

So what is our suggested approach to building the soundscape for a 360 video? It consists of creating the same kind of interactive audio structures as illustrated previously, and using the combination of viewpoints and parameters from the video to inform the audio playback (instead of the simulation data from the game engine). Music is the first element of the soundscape to benefit from this approach. As an example, the effectiveness of leitmotivs is closely tied to the their timing in relation to the appearance of key characters in the field of view. This simply cannot be achieved unless music is controlled interactively.

Another element is the audio mix itself. As an example, you can picture standing on a beach looking at the waves, then away from the ocean to look at the city on the other side. A film director would almost certainly request greatly contrasting mixes depending on what the focus of the camera is, while a purely spatial rendition would simply influence the positioning of elements.

In the end, it is fairly easy to see that this single degree of freedom is enough to warrant a serious look at sophisticated interactive audio methods. This is the natural thing to do when a game engine is used to render the experience, but I expect that at least some of these techniques will become available to 360 video content distributed through on-demand channels; they are necessary to deliver the level of experience that the audience expects. It’s an interesting return to having a live improvised performance accompany picture in film, as was the case in the years of silent cinema.

This article was written as a contribution to the book New Realities in Audio.

New Realities in Audio

A Practical Guide for VR, AR, MR & 360 Video

By: Stephan Schütze, Anna Irwin-Schütze

Comments