Music for video games is inherently different from that for linear media. The compositional requirements of linear and non-linear music are also very different. When Howard Shore wrote the soundtrack for the Lord of The Rings film series, he already knew which characters would appear on screen 20 seconds or 20 minutes in, and so could therefore combine leitmotifs, and properly trim the music in order to support the specific conditions of the frenzied scenes of the battle of the two Helms, or the peaceful sequences of the hobbits hanging around in the Shire, happily smoking pipe-weed.

Video game composers don’t get this luxury. Apart from cutscenes, they don’t have control over what players are going to do and experience in a game. But matching music with narrative is still a central aspect of video games. At its most extreme, the whole history of video game music can be seen as a continuous search for compositional techniques and audio tools that create a musical experience tailored to the visuals and narrative – in its own way as effective as that found in movies. In order for this to happen, the music must adapt according to the gameplay. Adaptive music techniques developed over time involve, by degree, complex modulations in an array of compositional and production parameters such as pitch, form and effects.

Composers have long known that music for video games music should be adaptive in order to enhance the experience of the players. Beyond being an insight coming from the trenches of video game making, this theorem has a sound theoretical basis. We can think of a video game as a dynamic combination of a number of components: visuals, narrative, interaction, and audio (see figure below). When the different components point in the same direction, they reinforce each other, and as a consequence, enhance the game experience.

A video game can be thought as a system comprising a number of components, which interact with each other with the goal to produce the game experience.

In order to coordinate music with the other components of a game, we must use some form of adaptive music. As reasonable as this may sound, surprisingly, there’s not much quantitative research to back it up. Also, little data-driven research has been conducted to analyse the relationship between music and players in more general contexts.

In the remaining sections of this blog post, I’ll share some of the quantitative findings we obtained from research we carried out at Melodrive. This includes surveys circulated among players and VR users, as well as discussion of a psychological experiment. The surveys gave us insight into players’ expectations and understanding of music for non-linear content. With the psychological experiment, we shed light on the impact that adaptive music, in the form of AI-generated real-time music, can have on players’ engagement.

What Players Say About Music

We conducted several studies to understand what video game players and VR users think about music in non-linear media. Specifically, we wanted to get insights into the following issues:

-

How important is music for gamers?

-

Are players aware of adaptive music? How much do they care about it?

-

Are players satisfied with current music solutions?

-

How would players like to engage with music?

In order to answer these questions, we carried out surveys among different demographics: VR/AR users and traditional video game players, Roblox users, High Fidelity users, and VRChat users. We circulated the survey on subreddits and Facebook groups connected to our demographics. 179 players filled it out. After we got the responses, we consolidated the results. Let’s take a look at the data that came out of it!

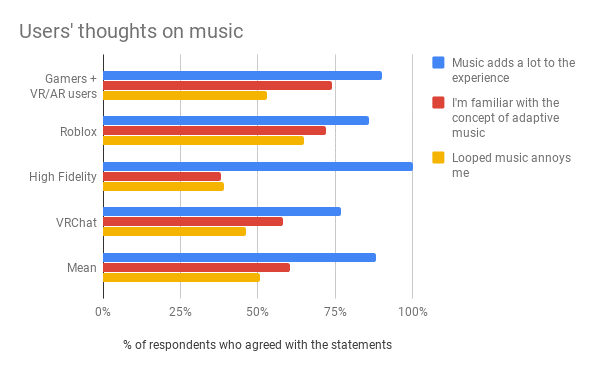

Players’ Thoughts on Music

Players think that music is a central aspect of gameplay. More than 80% of our demographics think that music can add a lot to the game experience. Players are also aware of the different types of music techniques that can be used in interactive content, and have strong opinions regarding what they think may or may not work. Approximately 50% of respondents told us that looped music is annoying. Some of them re-iterated in the open comment section of the survey that they would rather switch off the music than listening to the same, unchanging loops. A somewhat surprising fact is that approximately 75% of gamers and VR/AR users are familiar with the concept of adaptive music. They are able to recognise basic adaptive music techniques, presumably through the experience they’ve acquired playing games featuring dynamic soundtracks.

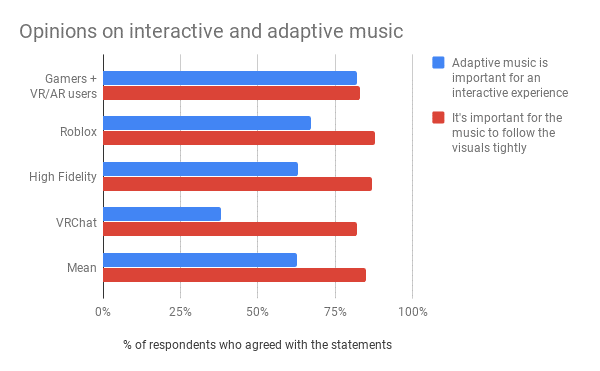

Players’ Opinions on Adaptive Music

Players are likewise opinionated about the role and the type of music they expect in an interactive experience. More than 60% of respondents think that adaptive music is important to enhance the experience of interactive content. This figure raises to approximately 80% in the players and VR/AR users demographic. A strong majority of people (>80%) think that it’s important to have the music matching other game components such as visuals and narrative. This data, once again, suggest that players are not only aware of adaptive music, but that they have a (perhaps) intuitive understanding of the dynamic requirements of music in a non-linear context. Not surprisingly, the opinion of players is consistent with that of game music professionals, who think that music in video games should be aligned with other game components, and therefore be adaptive. Is there something more to this, than just a well-educated opinion? We’ll get an answer to this in a few paragraphs, when we’ll look at data from our psychological experiment.

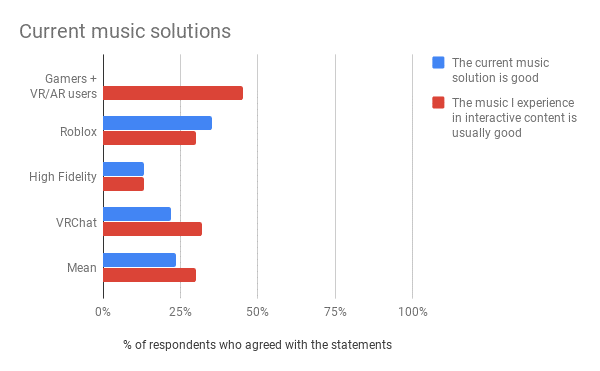

Players’ Thoughts on Current Music Solutions

From the study, it emerges that players rarely find their musical expectations met in the experiences they engage with. This is particularly true for new gaming platforms and social experiences, such as Roblox, High Fidelity, and VRChat, where less than 25% of users think the current music solution is satisfying. This figure is more encouraging for more traditional players and VR/AR users, where approximately 45% of respondents think the music they experience is usually good. The difference between new platforms and more established games can be explained by the fact that, in the latter case, there is a long tradition of music making that is able to deliver an overall better experience. Still, the figure remains quite remarkable as it basically suggests that there’s a lot of room for improving the musical experience of players in video games and VR experiences. By comparing this insight with all the other data points emerged from the survey, we can infer that players would probably like to have music that presents a better interplay with other game components.

Players’ Involvement in Music Customisation and Creation

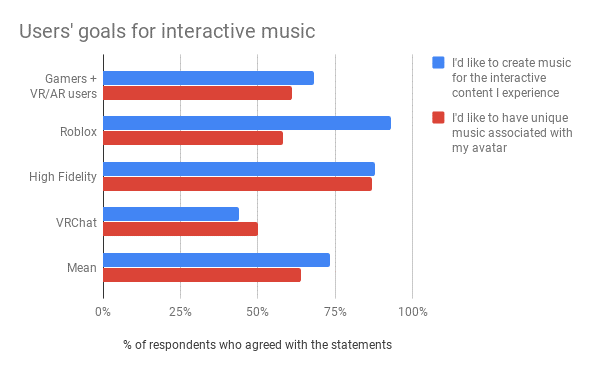

Respondents indicated a strong preference for being actively involved in the process of music customisation and creation. Specifically, more than 60% of people suggested that they’d like to have unique music for their avatars and the content they build in sandbox environments. Valve was one of the first companies to acknowledge this trend, by offering music kits for Counter-Strike. The players can go to the game marketplace and buy cues in different styles as downloadable content. These tracks help customise the players’ musical experiences in the game. Even though the music kits can’t offer unique music, they provide a significant degree of customisation.

The importance of music customisation becomes even more significant when we look at another figure emerging from the study. Almost 75% of the people surveyed said that they’d love to create music for the interactive content they experience, if this was simple to achieve. There is a deep-rooted need for people to use music as a way of expressing themselves in video games. However, arguably there are currently no robust enough tech solutions in video games to enable people – potentially with little or no musical skills – to create complex music. For this to happen, we need to integrate cutting-edge AI music generation systems directly in video games. What is remarkable about this finding is that none of the respondents has played around with such a technology, but they still see music creation as an important potential aspect of a game.

From these studies, we’ve learned a wealth of information about what players think about music. Players are generally very knowledgeable about the role of video game music. They expect the music in interactive content to dynamically adapt to the visuals and the narrative experience. However, music as currently found in non-linear content isn’t particularly well-received. Finally, players would love to be more involved in creating the music world of the content they experience.

Now that we’ve had a look at what players say about music, we should take the next logical step: analysing the mental impact of video game music on players. To do that, we conducted a psychological experiment.

What Players Feel with Video Game Music

At Melodrive, we’re building an AI music engine that can generate music, from scratch, in real-time. The music created by the AI adaptively changes its emotional state on the fly, in order to match the affective context of a video game scene. The rationale behind the development of this tech is a theorem that we’ve already encountered at the beginning of this article: the more the music aligns with other game components, the more the player will be engaged. Following this principle, we can claim that in a video game context, human-composed adaptive music provides higher engagement than linear music. To continue this reasoning Hybrid Interactive Music (HIM), as introduced by the game composer Olivier Deriviere, where pre-recorded stems and real-time synthesis coexist to provide a highly adaptive musical landscape, is arguably more engaging than traditional adaptive music. Again following the theorem that more alignment equals better engagement, we can claim that music generated by an AI that adapts emotionally to the game parameters in real-time (what we at Melodrive call Deep Adaptive Music - DAM), has the potential to increase players’ engagement even more than HIM.

Instead of trying to prove this chain of inequalities, which makes sense in a theoretical way but is difficult to validate as a first step, we focused on an easier task: proving the impact of music on players’ engagement. For this, we considered the impact of two types of music discussed above that lie on the extremes of the adaptivity spectrum. We devised a psychological experiment to track players’ engagement with linear music and track their engagement with DAM in a simple VR experience. We also had a control state, no music in the VR scene.

Hypotheses

To measure engagement we tracked two measurables: time that people would spend in the experience (time session) and perceived immersion. A number of hypotheses were implicitly derived from our theorem:

-

The presence of music increases the level of perceived immersion in a VR experience.

-

DAM increases the level of immersion more than linear music.

-

The presence of music increases the time spent in a VR experience.

-

DAM increases the time session in VR more than linear music.

-

DAM fits a VR scene better than linear music.

Experimental Design

To test our hypotheses we built a simple VR scene. The scene consisted of a space station with 2 rooms connected by a corridor. The first room (blue room) was peaceful and calm, the second (red room) was more aggressive. We modulated the mood of the rooms (tender vs angry) by using different lighting and levels of activity in the respective objects present in both rooms.

We set three experimental conditions. Participants could explore the VR scene with no music, linear music, or DAM. For DAM. the music was generated in real-time by the Melodrive engine. For linear music, we recorded approximately three minutes of music generated by Melodrive in a single emotional state. The linear music was looped in the VR scene during the experiment. The music used was in an ambient-like style with electronic instruments. Have a look at the table below for a comparison of the three conditions.

No Music |

Linear Music |

Deep Adaptive Music |

A simple VR space station scene |

Same VR scene |

Same VR scene |

Two rooms connected by a corridor |

A fixed, looping soundtrack |

Same sound design |

No Interactive objects in the scene |

|

Composed in realtime by Melodrive |

|

|

|

Each room has its own mood |

|

|

|

Music adapts to the mood in each room |

46 participants took part in the experiment. We didn’t tell them what the experiment was testing, so they didn’t get primed. Participants experienced only one of the three conditions and were instructed to explore the scene for as long as they liked. We tracked time session as an overall measure of engagement. Once participants were done exploring the VR experience, they were asked to fill out a questionnaire to gauge their perceived immersion. The questionnaire consisted of a number of standard questions that are generally used in psychological investigation to measure perceived immersion.

Results

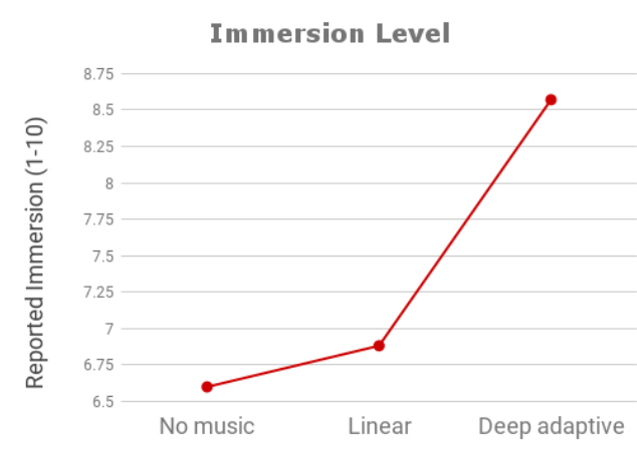

The initial hypotheses we came up with were found to be true and supported by the empirical results. As an aside, all the results I discuss next are statistically significant (p<0.05). The effect of DAM on immersion was huge. Indeed, DAM provides a 30% increase in immersion when compared to no music and 25% when compared to linear music.

Immersion level perceived by participants in the 3 experimental conditions.

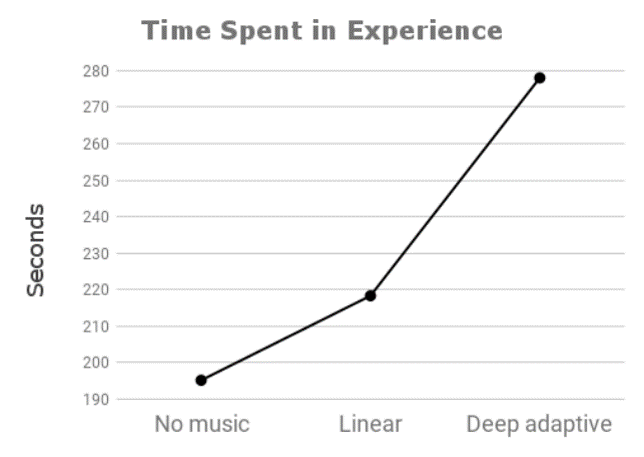

The effect of DAM on time session was even more significant. With DAM there’s a 42% boost in time spent in the VR scene over no music and a 27% increase over linear music.

Time spent in the VR scene by participants in the 3 experimental conditions.

90% of people agreed that music was a very important component that helped them feel immersed. Data showed that DAM contributes significantly more than linear music to the feeling of immersion. We also found that DAM increases the fit between music and the VR scene by 49% when compared with linear music.

Being a composer and a gamer myself, I was already convinced that music, being an effective medium to convey subtle emotional cues, would have a major impact on engagement. But perhaps the most striking element that arises from the experiment is not the huge impact of music as a whole. Rather, it’s the big difference between the impact of linear music and DAM. Of course, we were expecting DAM to have a stronger effect on immersion and time session. But we couldn’t imagine the difference would be so remarkable. This result suggests that deep adaptivity is what really makes the difference for engagement. In other words, a significant increase in players’ engagement is not automatically granted by having (any type of) music, but by having the right type of music, i.e., music highly synchronised with other game components. This is strong empirical support for the alignment-engagement theorem, which we’ve discussed above.

The preliminary results of this study have already been published at an international workshop on digital music. Check out the conference proceedings (our paper is at page 8), if you’d like to get more details about the experiment.

Conclusion

Despite the extensive research carried out by academics and practitioners in video game music, we still have a limited understanding of the relationship between players and music. Knowing what people expect from music in a game can help us design better musical experiences, which, in turn, can enhance players’ engagement.

Among the different results of the studies I presented, three points give us a privileged insight into the relationship between players and music. First, players are knowledgeable about video game music and are not very satisfied with what they currently get. Second, highly adaptive music can significantly increase the engagement of players. Finally, players would love to be involved in music creation and customisation. Trying to satisfy these player’s needs could open up great opportunities for composers and audio directors alike, and could lead to new forms of monetisation, such as DLC for music.

The overarching theme coming out of these studies is that music plays a central role in video games. Beyond our relatively small community, this point is not necessarily common knowledge. I’ve had too many conversations with game developers from studios at all levels, from indy to AAA, who’ve told me how music is a simply a nice-to-have feature for their games, that enters their thought only in post-production. For some of these people, linear music with a few crossfades here and there will do the job. They don’t realise how much they’re missing in terms of players’ immersion. It’s our responsibility to convince them that they’re wrong, and to provide them with a compelling narrative explaining why adaptive music is a key element for enhancing players’ engagement.

If you’ll ever be in such a dialectic stand off, these new quantitative results could help you win your battle, which, in the end, is a battle that if won could greatly enhance players’ game experience.

Comments

Nikola Lukić

November 14, 2018 at 03:05 am

Thank you for this article. This info is extremely useful. I'm very excited about future of AI music. Wish you the best in making Melodrive.

David McKee

November 14, 2018 at 12:24 pm

Wow that was an interesting article. I do enjoy when games have interactive dynamic music. Sometimes it's put together so well that you don't even notice it at first and it feels like you just HAPPENED to do something when the song was at a certain point. I think this is when it's implemented the best. It's put together so well that it just feels natural and not just a track cross-fading from one instrument to another. Batman Arkham Knight does this really well. (Don't know if it uses Wwise, but still).

Jon Esler

November 14, 2018 at 01:43 pm

I've known intuitively that adaptive music would make a huge emotional difference in the player's experience. The problem was how to achieve it. Not being a programmer I thought music stems could be combined and triggered by various scenarios and characters as the game progresses. Maybe they can? But AI is a much better solution as it could interpret the inherent emotion in a given scene and spontaneously compose or "remix" a piece for the scene using pre composed stems. What fun!

Valerio Velardo

November 16, 2018 at 02:31 am

Thanks Nikola! Indeed we believe that AI is going to be a game changer in music for non-linear content.

Valerio Velardo

November 16, 2018 at 02:34 am

Thanks David! As my composer friend Guy Whitmore uses to say "adaptive music is not only important for games, it's mandatory!". Interactive music can really make the difference.

Valerio Velardo

November 16, 2018 at 02:38 am

Thanks for the comment Jon! What you describe is human-composed adaptive music. For that, Wwise is by far the best engine out there, which will help you set triggers, states and stems, without too much hassle. If you want realtime music, to make the sountrack as seamless as possible, you necessarily have to go with AI.