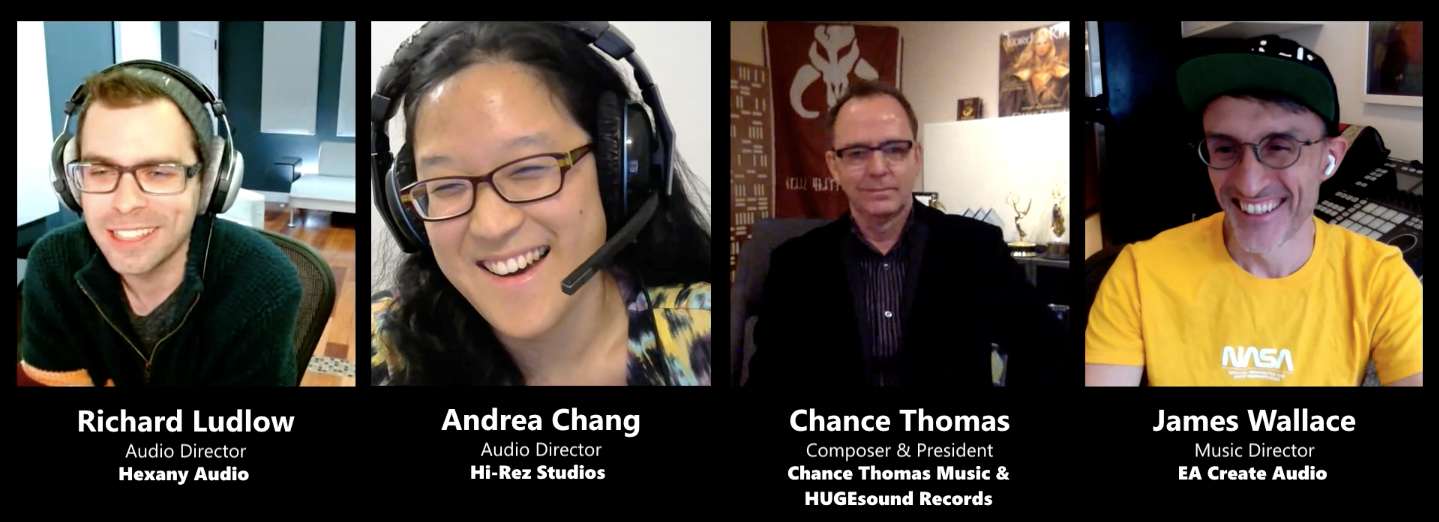

During our recent Interactive Music Symposium, we were joined by Richard Ludlow, Andrea Chang, Chance Thomas, and James Wallace. They came together to discuss music outsourcing workflow tips and tricks, as well as overall advice for sound designers and composers trying to get their foot in the door today. The discussion offered unique insight, as it included individuals from both sides of the table; James and Andrea providing the Music/Audio Director perspective, and Richard and Chance providing the perspective of a composer collaborating with a developer or publisher.

Where do you find composers? And how does a freelance composer find developers & publishers?

For Andrea and James - who work at Hi-Rez and EA, respectively - a lot of the composers they hire have been people they’ve connected with in-person over the last few years, from school, conventions, and other game studios.

As an independent composer, Chance agrees that personal relationships are huge. When first getting started, a friend of his told him, “it's not what you know, it's who you hug,” and he’s found a lot of truth in that. When attending conferences like GDC, making appointments with Audio Directors ahead of time has been top of mind. He finished by saying that, “being successful as a composer in the game industry is building relationships with people who are in a position to hire you. And you do that with your friendliness, and you do that with the quality of your work.” At Hexany Audio, Richard mentions that it's largely in-person relationships, returning clients, and referrals that are the main sources of new work for them, but he’s interested in seeing how things change into more digital formats over the next few years.

Assuming that personal relationships & conferences are a good way to make an initial introduction, what makes you end up picking someone?

For Andrea, the music ultimately speaks the loudest because it’s the end product, but the human portion is important as well. If someone is a brilliant composer, but really hard to work with, that could be a deal breaker. So, how do they receive feedback? How do they tackle revisions? Do they get defensive by the feedback? Ultimately, for Andrea, it’s important for a composer to be collaborative & easy to work with, to understand that the project’s needs come first, to make sure that each iteration actually addresses the feedback received, to communicate, and to ask questions when you don’t understand something or simply aren’t sure. In regards to whether a composer needs to have previous game experience, Andrea thinks that's a little less important. She mentions that it’s good to have knowledge of games and implementation because it provides context to how you write the music, but ultimately, if the music is good, an internal team can handle fitting it into the game.

James typically looks for two things in a composer: quality and personality. He says, “we're all so hyped about making something, right? And we want to work with people who are as excited about it as well.” He mentions something big on his list is people who are interested in exploring the undiscovered areas, even if that sometimes means going down a rabbit hole only to realize that they have to get back out.

As a freelance composer, how do you set expectations to streamline the feedback process?

Chance thinks it's critical for a freelance composer to identify at the beginning of the project who the vision holder is. He also likes to put a limit on the number of official revisions in his contracts. He doesn’t do this to squelch creativity, but to make sure that both his team and the developer are using their time & resources efficiently. He says, “We don't mind going after one rabbit hole, maybe a little bit down two, but you don't want to be pursuing twenty different rabbit holes on your way to finding a great score.”

Click on the image to hear Chance's thoughts on setting expectations to streamline the feedback process

Richard mentions that Hexany Audio doesn't limit revisions, although they do say, “within reason, an unlimited number of revisions, as long as scope isn't changing.” He’s found that people like that feeling of security, even if they don't take advantage of it. He adds that in addition to the vision holder, it's important to ask if there are any other stakeholders above them that a composer might be beholden to.

Composers are always asking “Do we need to know how to implement our own music?” What does music implementation look like on the projects you've been involved in?

At EA, James says that music implementation is done almost entirely in-house, which typically means asking the composer to provide the stems, and then taking those elements and splitting them in-house. However, he mentions that for composers, working with middleware, or at least playing around with it a bit, can be really beneficial creatively, as “it helps you wrap your head around what is possible and makes our job [at EA] a bit easier.” Andrea agrees, saying it’s important for a composer to understand how to use Wwise at a basic level, because having an understanding of the dynamic elements of your music is helpful and may change how you would tackle composing. She says, “the content is half of the experience, and how it’s played and how it's triggered is the other half. You can also destroy a beautiful piece of music if it's not implemented correctly.”

Chance comments on the implementation side of things from a historical perspective. Back in the 90s when his team was first writing music for games, they would dream up interactive approaches to music and give those ideas to technology developers. So, it’s been fun for him to see this come full circle. Although he’s only actually implemented music himself in a handful of games, he’s been very happy to let audio development teams fine-tune and implement in-house because they know their game inside and out. In his opinion however, it is critically important for any composer working in interactivity to have an understanding of music design. To him, this means asking “how can we make music come alive, respond to the game, stay fresh & relevant, for the entire experience?”

How important is it for a composer to specialize? And conversely, is it easy to get pigeonholed into that specialty?

Chance and James both agree that having a specialty as a composer can be really valuable. James explains, "it's a pigeonhole perhaps to begin, but later on, as you develop those relationships, [people may be] more willing to let you explore other areas." And how does one break out of their pigeonhole? According to Chance, "target a game that’s different from what you’ve done before, get to know the Audio Director who can potentially open that door, create the music, and then throw the Audio Director completely off guard."

On licensing music and the recent shift to modern, electronic, hip-hop, or pop-based scores?

James finds that EA has been licensing a lot of music recently. Working in sports especially, he’s been noticing a shift towards modern, electronic, hip-hop, or pop-based scores. He's seeing a change in the expectation of what a score even is, saying “you can make it out of entirely licensed tracks, where you work with original artists, and have them remix or rebuild them; so it's kind of a pseudo remix/license thing going on.” Andrea adds that at Hi-Rez they're seeing the same thing, and she thinks it opens the opportunity to work with pre-existing music in a creative way, crossing the boundary between score vs. song.

As a freelance composer, what rights can you agree to hang on to?

Over the course of Chance’s career, he’s learned that most developers and publishers only need a few rights. And so, when he structures a deal now, he gives them all the rights that they need, but retains the writer’s share of performing rights royalties and rights to exploit music outside of the game industry.

Richard adds that personally, he hasn’t found many deals where Hexany Audio has been able to hang on to ancillary rights outside of the game. However, he considers the following very reasonable things for composers to write into their contracts: the writer’s share of performance royalties, portfolio rights (to put your music on your website & social media once the developer gives you permission), and credit.

He mentions that with some companies, however, it can be difficult to get legal teams to grant writer’s share. And even if the rights may be useless to the developer and publisher, teaching them that can be hard.

Do you let composers hang on to some ancillary rights?

For James, letting composers hang on to some ancillary rights is something that he likes to advocate for, and that's part of the reason why the recent licensing shift has been interesting to him. He thinks that when an artist creates a piece of music, they have an investment in it. And if that artist ends up with some rights to that music and knows that they can share it on their own networks and be able to monetize after-the-fact, it’s a win-win situation. “We get that artist, we get this great music, and we also have them promoting the music and its connection to our own products. I think there's something really cool in that,” he says.

Click on the image to hear James' thoughts on letting composers hang on to some ancillary rights

In Andrea’s experience, hanging on to some ancillary rights is easier for bands and artists that are more well-known. In general, for a composer providing a typical game asset, it's not common. Although she wishes it worked differently, from a legal standpoint, it's best for the company to have less liability. Richard sheds a little light on the reasoning from a developer’s perspective, saying “they're purchasing this music. And if [the composer] can take and license that into some other commercial, what's to say you don't accidentally license that into something that’s a little risque or off-brand with a developer?”

When applying for a sound design position, does having music alongside sound design in your reel negatively affect your application?

Andrea thinks it’s detrimental if you’re applying for a sound design role but your reel highlights music. She asks, “What is your focus? Where is your attention?” Although you may be brilliant at both, you should put your best foot forward based on what you're applying for. James agrees and suggests if music is your focus and you love sound design, why not make music that uses your sound design skills?

Thoughts on having composers contribute to music design?

James finds that this depends on the composer - how familiar are they with interactive music? It’s important to plan for heavy integration-style pieces very early on in the process, especially if you have a composer whose head is in that space. But for more linear pieces, he finds that it typically doesn’t have to be a long conversation. Andrea adds that having a composer come on in the beginning to help with the identity of the game, or to compose a main theme, is important because it helps inform the personality and often breathes life into the project. After that, the composer can typically step away until the game mechanics and levels are more fleshed out.

As a freelance composer, when would you like to be brought on to a project? And when do you actually get brought in?

Chance starts off by saying, "I think every person who wants to have a creative contribution to a game wants to be involved as early as possible, right?" The reality that he has experienced over nearly 30 years in the business is that a composer tends to be brought in early if it’s a highly adaptive score and there are a lot of interactive elements that need to be developed with the team. However, he says, "you tend to get brought on in the last three months or so if most of the music that you're contributing is just a single or layered loop and a few stingers."

At Hexany Audio, on projects that don't require a year of highly engaging interactive work, Richard personally likes to tell clients to bring his team on as early as they can for an initial discussion; “and then we just usually sit in their Slack for six to nine months, and do a meeting every two or three months to check in on where things are,” he says.

Click on the image to hear Chance and Richard talk about getting brought on to a project

With COVID restrictions, how would you suggest composers network or find developers/publishers?

Richard recommends that composers find conferences that developers attend, and then see if those conferences have robust meeting systems. James agrees and says that conferences are great, and getting involved in the chat, asking questions, and reaching out to the presenters afterwards are all good ideas. He says, “most people, including myself, are really open to conversation after the fact. And I think that's almost where there’s probably more value. You get more specific answers to specific questions. So, definitely, you gotta put the leg-work (or finger-work) in, just to stay connected with everyone.” He also tries to go out of his way to listen and respond to everything that's sent to him. If he thinks a piece of music has potential, but there's something that would make him pass on it, he says, “I’m very happy to be honest about it. With kindness.” Richard adds that when reaching out, you need to be respectful of people's time. You shouldn’t send a list of 20 questions or 50 tracks that you want feedback on.

Commenting on COVID restrictions, Andrea says, “as an introvert, I think it's actually easier now,” as meeting up with people has become more predictable and accessible.

Click on the image to hear Andrea's thoughts on networking during the pandemic

What skills do you want to see in sound designers you're looking to hire?

Both Andrea and James agree that implementation competency is important. However, one thing Andrea thinks is not talked about often is instinct. For her, this means having a good ear and good sensibilities, which can often be determined with an audio test.

What makes a good reel?

When crafting a reel, Richard and James agree that it's important to clearly outline (with chapters, for instance) what you’re offering instead of having one long video. Richard also thinks it's a good idea to have separate reels for sound design and technical sound design. And when you're applying for a position where you're expected to do both, he'd like to see both reels separately.

For composer reels, Andrea thinks you should put your best foot forward in the first 5 seconds of every track. In addition, she thinks that production quality is often understated. Although someone could be a great composer, if the synthestration is not there, it could affect how people perceive the music.

What do you look for in a technical sound designer?

Andrea mentions that for technical sound design, something that she likes seeing is if the person applying is curious and/or has their own projects. Anything "showing some curiosity into exploration,” she says, "because I think that is a big part of technical sound design - can you problem solve? Not everything will be linear with technical issues."

Final thoughts & advice for freelance composers trying to get their foot in the door today?

For Richard, this might look like tracking down some games that are announced but unreleased, and sending a very brief but crafted message expressing his love for the project.

Andrea’s advice is to not give up. She thinks that a lot of the time, it’s about the mindset and setting reasonable expectations. She says, “set goals for year one. What do you want to accomplish? And then have actionable steps on how to get there. You may not hit those goals and that's okay, but at least you have a plan and you're working towards it.” She mentions how important it is to work on your craft, saying “it's like working out, you don't want to have flabby music muscles.” She then lists the 4 buckets she recommends composers fill: theory, production, networking, and business (e.g. knowing how to bill).

James mentions how he thinks it’s important for an artist to have a buffer with the money conversations. He says, “get away from any of that conversation. All you want to focus on is the creation of the art.”

Comments