Guy Whitmore, Composer and Audio Director at Foxface Rabbitfish dove deep into current industry workflows and standards while sharing his vision of the future during the 2019 Wwise Interactive Music Symposium. Guy shared how he is getting ahead of the game, by utilizing music design templates in Wwise. Here’s a rundown of key points from his presentation that composers should be thinking about as they continue to explore the role of interactive music.

The music's journey

Whitmore describes the typical roles in the typical linear order as they appear in the game music journey. The music's journey from pencil and paper to the game itself begins with Audio Direction and Music Design/Supervision. The music then moves along to Composition and Virtual Orchestration, leading into Orchestration/Conducting and Recording/Mixing. This is where the integration process begins using the Wwise Editor and Game Editor to then fully integrate the Wwise project into the game.

As we walk the path from sound direction to game integration, we see a high percentage of professional participation early on in that linear journey. Composition. Guy emphasizes the need to consider music logic and programming in the process of getting the game engine to work with Wwise, and ultimately best suit the story of the game. All of these audio roles and elements are key to a successful project, and the more they connect and interact, the better the game sound will be. Whether the team is in-house, freelance or a combination of both, you need a good team.

Guy emphasizes the need to consider music logic and programming in the process of getting the game engine to work with Wwise, and ultimately best suit the story of the game.

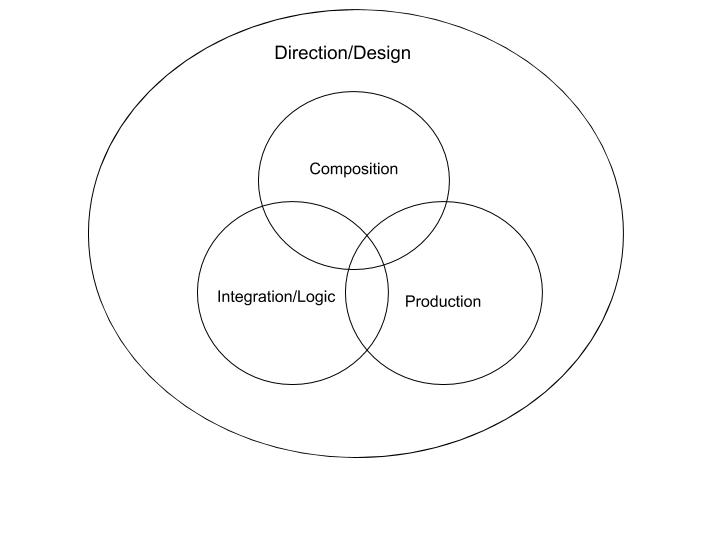

Guy illustrates the ideal collaborative process in the diagram below. Holistically thinking of the design of Direction. There are very real barriers for composers having real influence on the sound of a game and the overall music design. When you’re thinking of the direction of the music you're not just thinking about the kind of music, but how it will motivate the player, how it will move the game along and how it will interact with the various parts of the overall experience. This ideal collaboration across teams holistically captures design and direction.

When you’re thinking of the direction of the music you're not just thinking about the kind of music, but how it will motivate the player, how it will move the game along and how it will interact with the various parts of the overall experience.

Closing the Gap

What we are finding is that there are hundreds and hundreds of composers looking to do that small percentage of the overall work but there’s less than 1% who have the ability to do the music design and integration.

While there are many composers up for the task of writing interactive music and all of its components, Guy suggests that there are far less who have the ability to handle the music design and integration. He explores the immense opportunity to bridge gaps with composers learning integrations and processes. Standard working practice for hiring game composers, especially freelance game composers are queue sheets along with some images for inspiration. How do we close the gap between the composer and the game and then the game client? As it stands today, the process is transactional. The composer gets paid, score to picture isn’t even necessary, then the work gets handed off to someone else who then takes care of it. (Maybe the composer even gets to make a soundtrack!). However, he suggests that with this process we are doing the industry and the games that we are writing for a disservice. As the composer, even if you are not the one doing the music integration, your input is important in that decision making process. This is where the role of Music Design comes in.

Music Design - Doing more for your clients

It’s often said that integration is too technical for a Composer who is used to linear composition. Which Guy finds interesting, as composers are already in the full-embrace of what technology has to offer. The tools for interactive music integration are simply different and often approached with a different mindset. Wwise, just like any tool, has a creative outcome in mind.

Music Design is the act of creatively thinking about where the music should go and how the composer might want the music to support the intention of the game. This thought process is purely creative and happens before any technical work is done. Prior to thinking about any technical considerations, the Music Designer is imagining what should happen where, when and how in the context of the game. Guy explains how he now freelances, offering Music Design as an addition to composition. Outside of this role being a beneficial decision to the creative process, it is also a smart business decision. By adding this expertise, the range of clients which can be served will expand along with the synergy of the collaboration. Indie games are a clear example of how small teams do not always have that expertise at their disposal. Guy believes that It behooves Composers for games to have at least an understanding of the entire production chain, even if you have the support from a programmer to do the full integration.

It seems widely assumed that all complex and interesting adaptive scores would require a programmer, when in reality it only requires good communication with your development team and the imagination for greatness. Communication and understanding the collaboration process is key. Any wild, outlandish ideas can come to life when working with the programmer, developers and designers. Guy himself continues to learn some of the deeper systems like Blueprints for Unreal and C# for Unity to add depth and understanding to aid in clearer communication with his partners and clients.

Streamlining the process - Wwise Music Templates

Templates! There are always timelines to consider in the process of building the game. In order for the teams to implement these adaptive and creative ideas, Guys ultimate goal is to streamline and bridge that gap. It’s important to be able to design and implement quickly. When the company simply does not have the design and programming resources an implementation can fall flat. Not because they don’t care to go deeper, but simply because there’s nothing left to give. The goal is to be able to pull up to a company, plug into a project, and get it working in days. Vertical remixing templates, horizontal re-sequencing templates, sample instruments, event sets, and states, switches and parameters can all be built. When creating a Wwise project from scratch or from an import, using already existing recipes is the most simple solution. Templates are the building blocks and DNA used to build those recipes which you then adapt to the specifics of the new project. With the proposed process for Music Design using templates that Guy outlines, it’s entirely possible. We can then take away the heavy lifting of integration from the developer because sometimes, even if they want to help, they might not be able to.

From Templates to Recipes

Guy describes what he calls macro-templates. There are two areas of what he calls Music Design that have not been the focus for most of what you read in textbooks. Small concepts like Layering are commonly shown as an example whereas zooming-out and using the entire game to contextualize template formatting is the next challenge. He demonstrates examples of the pieces that comprise a template in his presentation later on and these examples become recipes for moment-to-moment adaptive scoring. Up until now, the adaptive scoring has been more focused on the minute-to-minute gameplay scoring, such as traveling music. Guy is interested in seeing what can be done with the broader-stroke moment-to-moment gameplay scoring, so he has been experimenting with this concept. Guy’s golden rule is to keep it as simple as possible to achieve your goal as the composer in support of the experience. It’s all about the game and what the player takes away from it.

A great example of micro and macro templates work was illustrated using the Peggle 2 project. Peggel 2 was a fairly deep adaptive score and the gameplay loop was similar no matter which character was played. Each character has their own set of music that was written according to a specific template or recipe that was defined over the course of development. Once the project was further on, Guy wanted to bring in different creative perspectives on these recipes, so cohorts Becky Allen and Stan LePard were commissioned to write additional pieces. They had to follow the recipes that had been established to support what the game needed. After a quick education about how the Peggle system worked, they then went off and composed for their unique character. When they sent their work in, fully completed Work Units (.wwu) were delivered to Guy who was then able to drop them right into the game and have them work right away. This experience helped reinforce that working with micro and macro templates and recipes not only streamlines development but empowers the additional composers with a clarity for the systems they were writing interactive music for.

Follow along with the rest of this video for a walkthrough demonstration with specific Music Design techniques that minimize some of the challenges outlined above. The ability to deliver game music within Wwise, via pre-existing templates, saves music integration and developer time. Additionally, well planned music designs also minimizes the amount and complexity of game calls needed from the game, thus saving developer resources and minimizing technical hurdles. Above all, it's a way for composers to gain creative influence over their music scores in an interactive context.

Watch the full video here:

Comments