This blog post is about using informant audio in video games and how to combine game design and sound design to gamify the sounds of a game, using them for both game design advantages and player guidance, or to further support the narrative. Except when specifically stated otherwise, all the examples mentioned are my own observations, and I have no affiliation with any of the mentioned games or their developers. I wrote this out of pure interest for game audio, game design, and using audio as an informant—not to promote any of the said games. Let’s get to it!

A spaceship parked at a wormhole waiting for somebody to arrive - the ability to listen for the activation of the wormhole is great game audio gamification.

Audio and graphics - we can allow each of these elements to have their unique mechanics in the gameplay and narrative

Video games have been around for quite a while now. Graphics, gameplay, sound effects, and more are used together to create experiences, and it's been quite an interesting ride to witness all the developments that have been going on in all of these fronts, separately. Unfortunately, a lot of us tend to focus on one, perhaps two of these elements and neglect the others. That is a shame because it's their combination that creates the experiences.

Our minds are primitive and built around senses that are simply made to alert others or alert and warn ourselves of the dangers lurking around us. As a sound designer myself, I often take notice that we developers sometimes seem to not understand how we can help and support one another. This doesn't mean that any of us are bad developers; however, both sound and graphics can be taken for granted as support for gameplay, narrative, and such things. But, with technology and the ability to use sound and graphics in the ways available to us today, it has now become more possible than ever before to allow each of these elements to have their unique mechanics in the gameplay and narrative. This is not about one being better than the other or pointing fingers and saying that either gets more attention than the other, or one should be less important—on the contrary, this is an attempt to raise the bar and elevate the cooperation among the talent to create the ultimate video game experience.

In several documentaries on the subject of video games, sound design has been placed as the evil sister of the development process, something that is required but quite often misunderstood for its actual purpose and needs. (1) I wrote a thesis during my studies at university (2) while I was already working as a professional sound designer in video games, and I took note of the lack of writings on the subject in relation to combining sound with visuals rather than using it as support for it.

Hacking in EVE Online - the ability to hover the undiscovered nodes and listen for their feedback is game audio gamification.

Just like in linear media, the misunderstanding that sound in games is simply support for narrative and mood put me off. Sound was still being analyzed and treated as it was in linear media, even at video game studies. I also noticed that this was sometimes the case at studios I worked at. This doesn't mean that all the other developers "didn't get it", but it was more an artifact from previous times where sound was something limited and difficult to control because of computer power and because somehow we've been stuck with this idea and not taking advantage of the possibilities.

As a former art and interactive media student, I noticed some of the possibilities in treating sound in games as interactive art, kind of like an interactive art installation, by obtaining data from any form of interaction and providing feedback, in this case through sound. I called these audio informants and tried to find all the different ways we can use them in games, as direct informants linked directly to game events in pre or post, as immediate forms, or as indirectly linked sounds to events which could be just as helpful as the direct ones, as well as ways that were more hidden or linked to more obscure game parameters or events. When gamifying a soundscape, it is important to have a clear understanding that not everything can or should be an informant, and that lots of sounds should stick to their primary task of supporting the narrative and the desired mood.

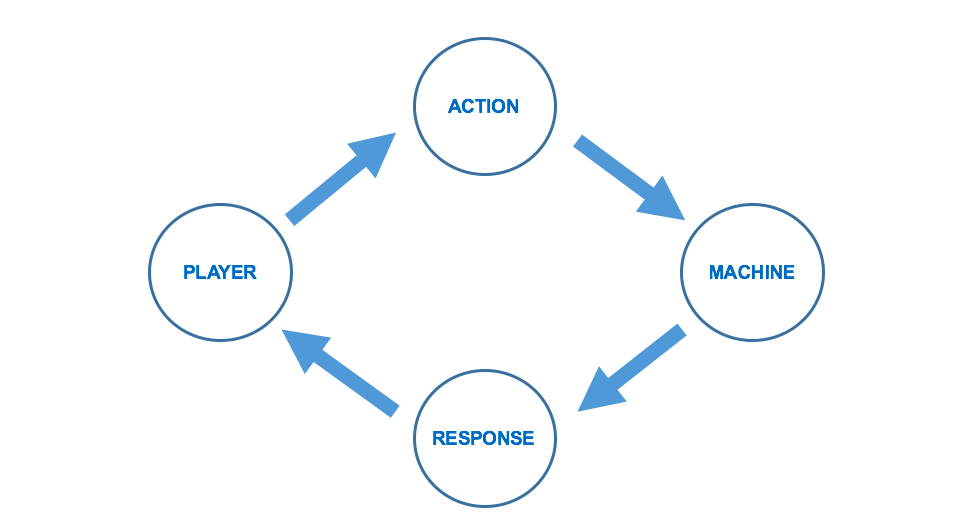

Constant conversation between the player and the machine

Steve Swink, in his book on Game Feel, explained quite well how communication between game and player happened, and that different from linear media which could be classified as a monologue, games with their constant feedback to any player action could be classified as a dialogue. I called this the constant conversation between the player and the machine and, to clarify the process, I linked it to the various communication models that exist about verbal and digital exchange of information.

The constant conversation model below is basically a combination of all the basic communication models; these are monologue, dialogue, consultation, registration, and more. And, any combination of them together.

The constant conversation - Player performs action, game responds, player receives, and new action / reaction / response - repeat. (2)

Informants: direct, pre, post etc.

Let's try to explain the differences between the various kinds of informants with a few examples.

In the brilliant crime solving detective open world adventure L.A. Noire, there are some great examples. There is a small piano chime whenever you, as the player and the protagonist, are close to evidence or points of interest during the solving of a crime scene. This chime sound will play as you approach the game object. And, if you already interacted with it or have interacted with other items that render this one irrelevant, then the chime will be slightly different; kind of like a positive and a negative feedback chime. This is a great example of a direct and immediate informant. While you can spend 'instinct points' in the game to see all the clues on the mini-map, it is possible to complete a crime scene 'easily' without a single use of this kind of help, just by walking around the area and listening for the chimes.

In the same situation, there is also a crime-solving piece of music playing, this only plays during the investigation and ends with an end stinger being played when the last piece of evidence or puzzle has been found or solved.

This is sometimes, mostly for combat situations, known as the 'victory gong' - a sound that clearly indicates the end of certain situations, which is also a great example of a very direct way of audibly explaining that you can now move on towards a new case or crime scene. In L.A. Noire the music also only plays in the actual crime scene area, so if you are walking around the crime scene and notice the music fade when going past certain points, you have now been audibly informed that the piece of evidence you are looking for is definitely not located in this direction.

The same kind of victory gong musical stinger or sound is used in many games. Uncharted, The Last of Us, Gears of War, and many others have this distinct music playing during combat and a distinct way of audibly notifying the player that combat has ended and you can now calm down and loosen the grip on your controller (if you play at high enough difficulties, of course). A victory gong is a great example of a post event informant, it doesn't tell you to do anything specific as much as it tells you to just stop what you are currently doing and move on. L.A. Noire also features a piano chime during interrogation game modes, where you as a player have to figure out the correct response to a question. This is also a post event direct informant as it only plays once you have chosen your action and regardless of the result, you cannot alter it at this moment.

The Last of Us (one of the best games I have ever played) has lots of informants, and they're similar to the ones in L.A. Noire. Combat music plays during combat and ends with a victory gong once over; but, more importantly, it also has a noise type sound very directly linked to the value which indicates if you are about to be seen by the enemy. This is especially useful in stealth situations and a huge direct pre-event informant. It is so perfect in The Last of Us that some stealth moments in the game can be completed just by listening, even with your eyes closed. Once seen by an enemy, the noise stops playing abruptly and a distinct "you have been spotted" sound plays as a direct immediate informant, and game play now changes into combat or however you wish to solve the current situation at hand. So stealth and combat in The Last of Us contains pre, post, and immediate audio informants greatly aiding the player.

It is important to mention that it is never explained during any tutorial or other moments that this sound is there to help you like this, but for some reason players seem to quite quickly understand and use it, even if they cannot explain or remember that they heard a sound that made them alter their actions in the game. The Last of Us team could have gone for a different solution and plastered arrows pointing where the enemy was coming from on the visuals of the game, or changed colors when close to being spotted, or other visual solutions. Visuals are not bad, but I believe that all arts, especially when combined in a game like this, can have a point of saturation. There is no point in overusing graphical UI elements if you can lighten the load on visuals with a sound and, of course, vice versa. I believe that this will provide a much smoother experience for the player.

Saturation, otherwise known as information overload

Saturation as such is also known as information overload, infobesity, or infoxication (or cognitive overload). There are several Wikipedia articles on the subject, but saturation basically describes the inability to make the right decisions when provided with too much information at one time. I’m sure there is someone out there who can describe it better than me. Consider this an invitation for someone to write their Ph.D. dissertation on the subject and find out how much information from each type, such as graphical, audible, and emotional, we can handle at one time when playing video games. (3,4,5,6)

And, obviously, as much as you can create graphical information overload, there certainly is a way to create auditory overload as well, making the information you want the player to perceive disappear in the mud of sounds. How to technically solve, mix, and fix this from an engineering perspective is for a different blog. I'll stick to theoretical observations for this one.

Graphical, UI, and information overload come in many forms and shapes. When enough is enough, or how much one can interpret, is very subjective and personal (just my personal guess). Playing World of Warcraft is quite different from watching others play it, at least in my case because I have no clue what is going on and all the individual styles of arranging the UI and icons of all their powers. I am definitely overloaded with information when I see others play it. I guess I am quite minimalistic when it comes to how much UI information I can handle. I also had a quite interesting conversation with a former UI designer colleague of mine from IO Interactive, Guus Oosterbaan (8), on the subject of UI and information overload, and he mentioned that 88 buttons on a remote control may be too much, but on a piano 88 keys is perfectly fine. Also, while a beginner piano player might feel more confused with 88 keys, an experienced piano player is not.

Actually, this is the same experience I get every time someone who is not familiar with sound design or production comes to my place and sees a multichannel mixer. “How do you keep track of all those buttons?”, they ask. Yet, to me, it’s perfectly clear which button does what, and I know that there is a system and that I only need to understand one set of them to understand all of the rows.

All this to say that the same considerations must apply to sound, as a new person who has never heard a specific warning or alarm before might find it either confusing or just annoying as noise, until they learn of its use and how they can take advantage of the information received from it.

Got sidetracked on the UI information overload discussion, now back to sound and informants—in actual games.

Gamification and communication models continued

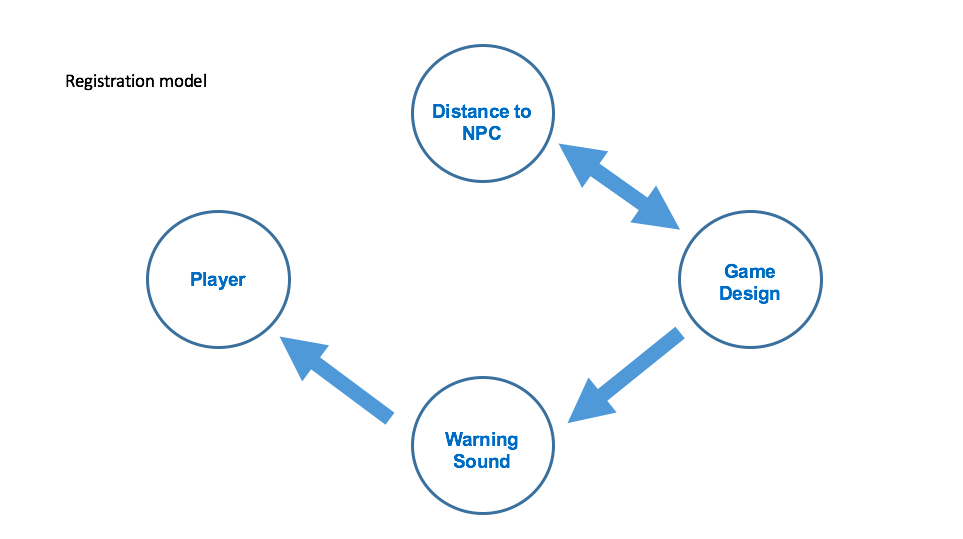

HITMAN Absolution also has a sound directly connected to a parameter indicating how close you are to being detected by an enemy, but also a visual indicator pointing out the direction to where the enemy is, but playing at higher difficulties removes the UI completely and the player has to rely on sound only, or just being really good at the game and knowing where the enemy is.

Registration model for The Last of Us and HITMAN Absolution. The games automatically register the players' distance to NPC (non-player character) vision, and provides a warning sound.

I have in quite a few talks mentioned these communication models and always described the registration model as “the big brother model”, primarily because it registers information about the player without the player knowing. This is not in a bad way, rather this information may be used to alter your game experience in so many ways, and not just through sound or visuals.

All these examples of great use of informant audio and how to gamify the sound design or combine it with the game design, are great for people who use sound to their advantage; but, just as with so many other things in life, your audience may play your game differently than you intended or simply have physical handicaps that can prevent them from experiencing your full plan of informants, be it graphical or audible informants.

So at the same level as the previously mentioned saturation, and that not all sounds should be informant or connected to vital parameters in the game, we should also consider if the game can still be played and perceived as a great experience if the sound is turned off. I don't encourage players to turn the sound off, you would surely be missing a great deal of the game, but players who are physically unable to hear your work should not feel that they are missing out or that they have a massive disadvantage when playing the game.

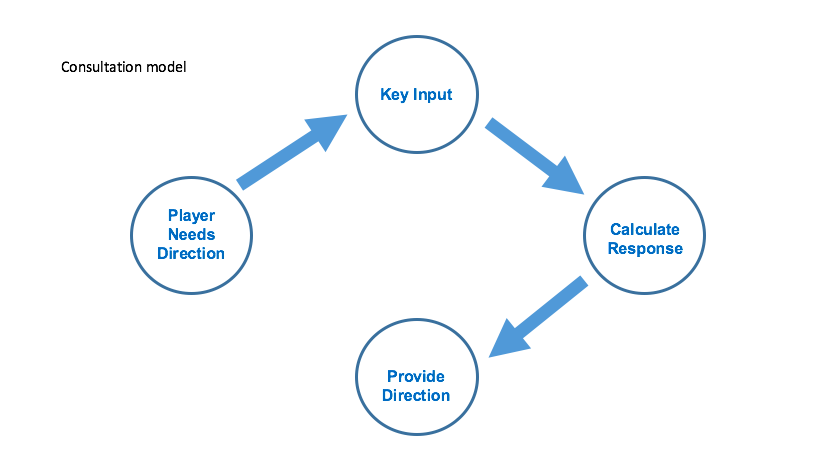

L.A. Noire also features a great alternative to a graphical informant and response, by not having the current route marked on the mini-map or directly on the road during gameplay when driving from location to location. Here it is possible to press a controller button which then activates a small dialogue sequence between the protagonists and their partner in which the partner mentions which action to perform next to go in the right direction, such as “go left next” or “continue straight”. This is a great way of avoiding plastering the gameplay in arrows or colors to show the way, yet allowing the directional information to become part of the games' dialogue, as well as a very direct informant about where to go next.

Consultation Model of L.A. Noire Guidance System - Player consults the game by providing the correct key input about directions - game responds with directions.

In using sound as an informant and creating a "listen to win" scenario, informant audio is merely a tool to create more links between gameplay and the sound of the game instead of just having sound as a layer for "mood".

More to come in part 2 of this blog! Stay tuned.

In the meantime, Informant Diegesis in Video games was my Ms. Thesis at Aarhus University.

Sound is important in all media; this thesis focuses on the use of sound as a method of grabbing the attention of the player and guiding them through the game. Simply put, using sound as an informant to support game design or create its own piece in the game design puzzle.

Comments

Bjørn Jacobsen

April 25, 2018 at 05:27 am

In case you want to know more: I recently made this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cJoW9vpj4k About the use of audio cues and gamification in L.A. Noire. Enjoy.