Impulse responses are well known for ultra-realistic reproduction of real rooms. Recording impulse responses is somewhat technical and requires high-end equipment to achieve the best quality. Creating outdoor impulse responses with spatial qualities is yet another challenge. But we sound designers all know: putting a sound emitter outdoors in an acoustically-believable & immersive way is a really tough challenge.

What are Impulse Responses?

To put it simply, an impulse response is used as a stand-in for a natural reverb. More technically, it’s a measurement of how a system or space responds to a very short sound or dirac spike, a direct impulse that can then be used in a convolution reverb plugin to recreate the acoustic characteristics of a place.

There are two other techniques which require a bit more computing to create an actual impulse response: recording a noise sequence - you might have heard something like that already when a device (be it professional studio equipment, consumer hi-fi or even game consoles) measures a room to either optimize speakers or to be able to locate a sound source, a.k.a. the player (Microsoft Kinect), in a given room.

The third option, probably most well-known in professional music and sound environments, is to record a sweep that (ideally) covers all frequencies evenly over time.

Recording an impulse is the easiest to use, because it can be used as an impulse response right away - that is what it is, after all. The other two need some engineering to fold it down into an impulse response.

What are the Pros? What are the Cons?

Impulse responses reflect the real room (except for measurement errors or coloring due to used equipment, both playback and capturing devices). It is ultra realistic, like a photograph.

And that right there is the con: a 3D object might not be as realistic, as nice, or as colorful as a photograph. But you can change whatever you want: you can stretch it, you can modify colors, or you can exchange parts of it. Impulse responses are limited. Of course you can do some things, like color-correction (EQ-ing), changes in dynamics, and you can also timestretch and pitch shift. But algorithmic reverbs can do much more than that. But it will still not be as realistic, as believable. In the end, the choice between algorithmic reverb and impulse responses depends on what story you want to tell, how you want to pull the player into a virtual world, if flexibility and creativity is more important than plausibility and realism in the style of the game / production.

The Great Outdoors

Usually in games you work with sound recorded in studios or with relatively generic spatial information to be able to place it in different locations after the recording. Often there are simply too many places in a game to be able to go out and record all sounds in each location (or a similar environment). Then you need to apply a reverb that mimics the natural sound echoes of the location of the scene. Not having the right reverb makes it all too evident that the recordings were done in the studio or not in the same location as the current scene plays in.

Normally, this is done by creating an impulse response. You go to the location needed, make a loud sound (impulse, noise or sweep) and record the effects (the response). Take that impulse response and convolve it with an audio signal; that is, by putting it into your convolution reverb plugin. Bingo, your sound now sounds as if it were recorded on location (of course, in theory, it sounds easier than what it practically is).

For some locations, it is extremely hard or even impossible to do this. If the location is too big, you’d need an outrageously loud sound to get a decent signal-to-noise ratio. If it’s in the middle of areas that are constantly crowded, like public squares, there’s simply too much interference. If it's an area that's hard to reach, you might not be able to get all needed equipment there. If it's a restricted area, it might be difficult to get permission to record audio. For our “Fields and Spaces - Outdoor Impulse Response” library we found a way to reproduce these locations and make it possible to capture it with all the spatial information, up to 3rd order ambisonic, with nearly zero background noise for extra high dynamics.

Spatiality

Recording an impulse response in mono is straightforward. You have a sound source (a speaker), and a receiver (the microphone). You put those in a nice spot in a room and capture the impulse.

Recording in stereo is pretty much the same thing: you put a speaker into a room but you capture it with two microphones, a nice stereo setup of your choice. Done.

With surround, suddenly some interesting artistic questions pop up: do you want the sound source within the surround field, being able to capture a rather evenly spread out surround image? Or do you want to place the sound source on the outside, suddenly creating a direction not only through directivity but also via time delays between microphone capsules (or later the playback speakers)?

With Ambisonic, this question is a bit obsolete, because Ambisonic microphones are coincident, thus you cannot place anything “within” the setup, all the capsules are at the exact same spot (again, in theory). So the sound source will be on the outside for sure.

Open Question to Spatiality

Now it gets more difficult. There is something called “true stereo”. That means in a room you do not record one sound source with two microphones (a stereo setup). If you place the sound source at a different spot within the room, the reverb at the same microphone location will be different. Place the sound source further to the left, the reflections of an imaginary wall on the left suddenly reach the microphone earlier compared to the reflections of the wall on the right (and tons of other shifted echoes). The direct signal also sounds different, more or less obvious depending on the stereo setup you are using. So with true stereo you are getting a bit closer to reality: you record not one sound source spot, but two. Imagine an orchestra in a concert hall: the bass on the far right can now get a different reverb placement compared to the violins on the far left. And you can create a mix of the two stereo IRs for everything in between the far left and the far right.

Obviously this is still not how it works in reality, but it is way closer and offers a much nicer, wider, and a more “understandable” stereo image for a human being. The downside is: it needs twice as much computing during playback, so it is two times more expensive for the CPU to play back. You in fact have two different stereo impulse responses playing back = 4 channels of reverb.

Surround: phew, what now? If you think “orchestra” again, that might be OK-ish - you do true stereo in surround: capturing two different spots in the front area. But that only works for this situation. If this is about sound effects which can happen in front of the listener, but also on the side or the rear, it gets more complicated. In order to get something similar to true stereo, for each speaker in a 5.1 system (a small setup), you would record a dedicated impulse response. Say we spare LFE and Center and only take front and rear: instead of four channels surround reverb, you suddenly have 4 x 4 = 16 channels of reverb - heavy lifting for the CPU.

Ambisonic: You might not need to create one IR per capsule, but the more sound source locations you record, the higher the spatial resolution. And you need at least the corners of a dice in order to capture 360° equivalent to true stereo vs. stereo. That makes it even worse: You now have 4 tracks (1OA) x 8 sound source locations = 32 channels of reverb. Unless your game is majorly using reverb as the main feature, this will be overkill for games in runtime. And that is only first order ambisonic. Talking higher order, say third order ambisonic, you have 128 channels, but also if you “only” use eight locations (the corners of the dice) for the sound source which for 3OA creates a lot of empty space without information.

Solutions

It seems like IRs are too complicated, too heavy for games after all - but that whole topic about spatial reverb is not limited to impulse responses, the same principles go for spatial algorithmic reverb.

So what now? First of all, the “true stereo principle” does not necessarily have to be translated into surround. It is more something to think about, to keep in mind in order to find the right spots in 3D environments to place and use reverb. Secondly, there are parts of a reverb that represent a location much better and parts that represent the position of the sound source much better, namely the tail versus the early reflections.

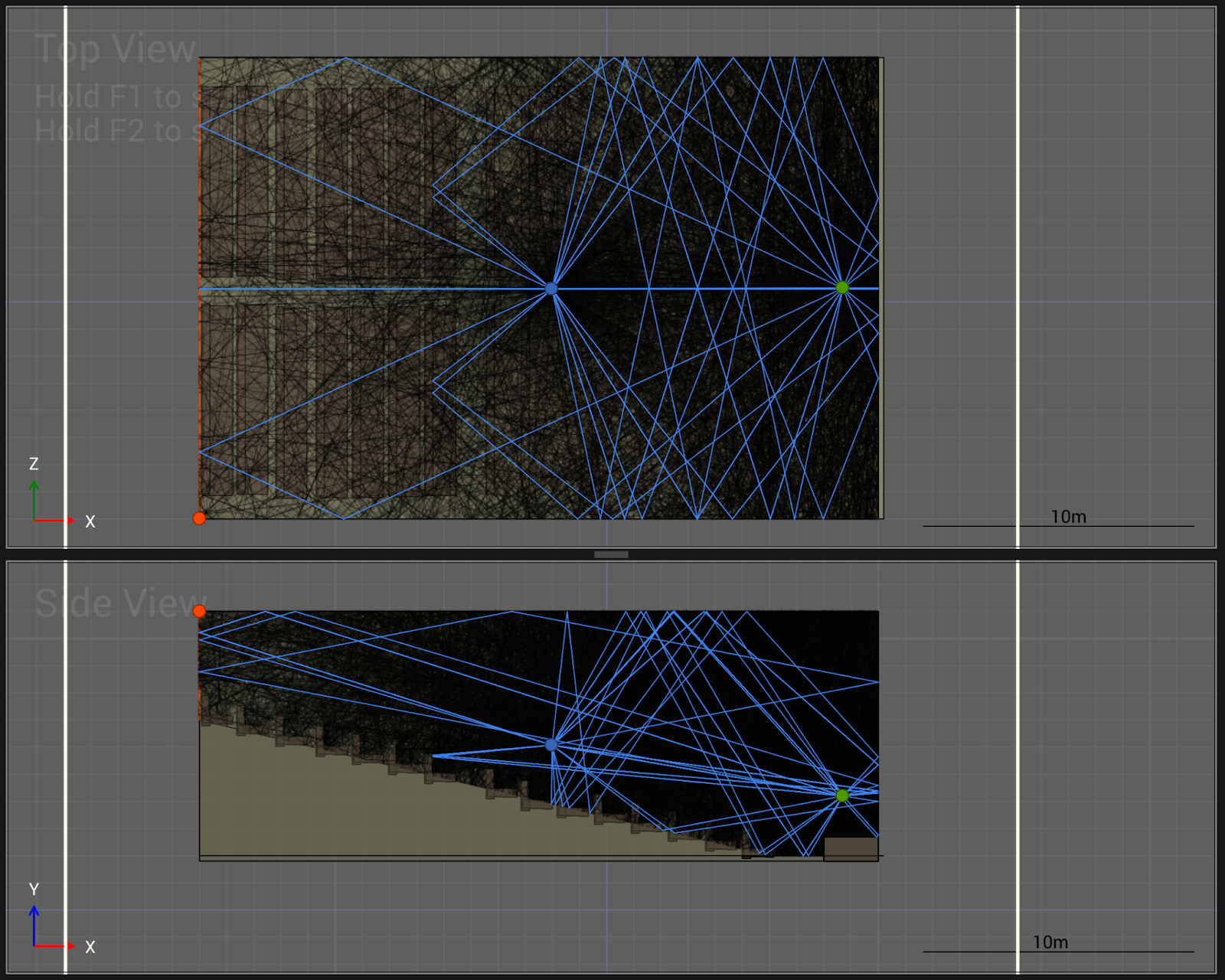

With our impulse response plug-ins “Rooms and Spaces”, and now “Fields and Spaces” as the outdoor variant, we strongly focussed on capturing the tail and a diffuse impulse response, trying to avoid early reflections. The early reflections are rather easy to compute because the amount of echoes is way less and in a shorter amount of time. Using, for example, Audiokinetic’s Reflect plug-in does exactly this: it can create early reflection based on actual 3D objects / sound obstacles in a game. Adding an impulse reverb for the tail creates an immersive, deep, flexible reverb which offers great locatability of sound sources even when in motion in runtime.

Comments