Since the first snippets of speech found their way into games in the 80s, developers have wrestled with the challenges of using the evocative sounds of language, human emotion and performance in a non-linear, interactive medium.

Just as it was once Composers who were expected to do Sound Design for the titles they worked on, Sound Designers were expected to work on Dialogue. This was oftentimes handed to the most junior members of the team as a cross between a poisoned chalice and a rite of passage!

However, this has been changing over the years with Voice Design (a.k.a. Dialogue, VO, or Speech Design) slowly becoming an established specialism in game audio. More recently, this evolution has rapidly accelerated, with many AAA audio teams either greatly expanding their existing voice teams or hiring new ones from scratch.

Voice as a Creative Tool

We are all subconscious experts in the human voice and understand implicitly when something feels wrong, for example: A line triggers too soon or too late, a reaction feels inappropriate for the situation, the language used feels broken, or a character switches moods in an unnatural way. However, our innate sensitivity to voice is also a bounty of creative opportunities.

Voice alone conveys an enormous amount of information beyond the actual words in speech. Many aspects of the human voice such as timbre, register, prosody, accent, idiolect, speech patterns, mannerisms, affectation and disfluencies can speak volumes about who a character is, what their ambitions or fears are, and even tell us about the world they live in.

Broadly speaking, voice is that quintessentially human component of a project’s soundscape, and it would be a bleak and lonely place without it. Once you start layering in the spectrum of utterances which comprise human activity, a location can quite quickly take on a vocal character all of its own. In this way, voice does world building in ways other sounds cannot.

The rate we feed this content to the player can conjure feelings of relief and security when entering a safe haven, build awe and disorientation when arriving in a new town, or describe the high stakes danger of a battlefield. The human voice is a powerful and intensely psychological tool. When used effectively, it can shape and steer how the player feels in ways composers could only dream of.

Behind the scenes of recording Tom Clancy’s The Division 2

A Specialist Linchpin

Developers spend millions on voice and dialogue, enlisting vast armies of outsourcers to bring their ambitions to life. This often includes voice and casting directors, voice actors, walla performers, recordists, dialogue editors, project managers, localization specialists, translators, localization QA and many others. Orchestrating this is challenging enough but with production and implementation having dependencies on almost every discipline on the internal development team, high-quality Voice Design is impossible without expert knowledge and experience.

To accomplish this efficiently, we need an Audio Design role which provides specialist, creative, technical, and production oversight. Acting as the nexus between the development team and our external partners, we deftly balance the sometimes contradictory needs of narrative and gameplay, but critically also understand how to use the voice creatively.

Voice is the fastest thing in any project to make your game feel old and cheap. It is essential for maintaining immersion, but also swift to break it if you aren’t careful. We wield it to its greatest potential and ensure it does not abuse the player’s ears!

We go by many different names such as Dialogue Supervisors, VO Designers, Dialogue Coordinators, among others, with Voice Designer and Dialogue Designer being the most common. While job titles may differ and responsibilities vary, our work extends well beyond recording and editing, which are commonly outsourced. Encompassing a broad range of specialized knowledge and experience that would take a lifetime to master, our work includes:

- Planning & Scoping

- Previz & Prototyping

- Barks Systems & Systemic Design

- Vocalization & Breathing Systems

- Crowd/Walla Systems & Environmental Voices

- Pipeline Design (VO, Cinematics, Walla)

- Database Management

- Outsourcer Coordination & Collaboration

- Constructed Languages

- Casting

- Script Proofing & Session Prep

- Recording & Engineering

- Performance Capture

- Voice Direction

- Dialogue Editorial

- Linear work & Cinematics

- Vocal Processing (pre-rendered effects processing for creatures/robots/etc)

- Mastering (EQ, volume leveling, de-essing, compression, loudness targets and broader stylistic processing)

- Runtime FX (realtime effects processing in middleware such as Wwise)

- Designing any associated SFX (eg: radio squelches or interference)

- Timing & Pacing of Scripted VO

- Dialogue Management (cooldowns, state driven playback behaviors, and interruption, queuing and priority logic)

- Localization Support

- Pre-mixing & Mixing

All of this places our discipline firmly at the heart of the development process, from pre-production through the entire project lifecycle. Even where there is no recording to do, there is always plenty of work to be done!

Creative Collaboration

Being an important communication tool and sitting at the intersection of audio and character, there is a great deal of collaborative and creative potential in Voice Design; whether it's working with the Cinematics team to manage the complexities of performance capture pipelines, or acting as an advocate for Localization teams to ensure they get the accommodations they need to do a great job. The multitude of departments and outsourcers we work with makes communication, collaboration and empathy essential skills for this very social role.

Game Design leans heavily on voice to communicate mechanics, telegraph threats and provide feedback to the player. A large part of our role is helping them achieve this tastefully so as to not break the player’s immersion. This means working closely with Gameplay, AI, Level Design, Animation and others to find creative solutions. In my opinion, this is one of the best things about working in games; working through our shared problems with talented experts from other disciplines and finding compromise wherever we’re at odds- it's a team sport!

This is especially true with Narrative Design, as it is this creative partnership which is responsible for our primary purpose: Dialogue! As the spear point for story on the audio team, we help them navigate the arduous process of bringing their creations to life, ultimately culminating in the recording studio. Together, we share the pure joy of working with Actors and Voice Directors to piece together the fragments of story and weave our characters into existence. In an open and collaborative environment with plenty of time to play and explore, the resulting performances can surprise us in ways our imaginations couldn’t devise.

Ensemble recording for Broken Sword 5 - The Serpent's Curse

However, creating a safe, carefree and easy going atmosphere for this creativity to happen (where Directors and Actors understand the project, world, character and context), while staying on track and within budget does not happen by accident. Making recording sessions seem effortless takes meticulous preparation and planning; it is carefully designed.

Putting the “Design” in Voice Design

If you want to do Sound Design for a weapon, you can’t just record some gunshots, author some assets, slap them in the game and expect them to work brilliantly on the first attempt. Voice is no different; whether it is sessions, systems, pipelines, features, casting or processing, there needs to be careful thought, design and iteration involved.

Context is king, and its absence is the cause of gaming's greatest dialogue failures. Actors need to know who they are, where their character is, what is happening and why they’re there. We need to provide comprehensive context whether it is scenes, barks or vocalizations, and it must be written precisely and intuitive to use. This is an iterative process, as figuring out how to communicate context for things like barks or vocalizations takes trial and error. This work is essential for making sessions creative, carefree (and quietly efficient!) places for great performances to happen.

When casting, performance comes first. We need to find actors who are appropriate for the role, understand their character, take direction well and have the technical skills to do the job. However, there are also design considerations to take into account. For example, we need to make sure that our main cast and secondary characters sound or feel different enough that the player knows who is speaking. Unlike film, we can’t control what the player is looking at! Then there’s the opposite problem with NPCs, where we need to make sure they sound similar enough that the player doesn’t notice how many times they encounter “Enemy Goon #6” over 30 hours of gameplay!

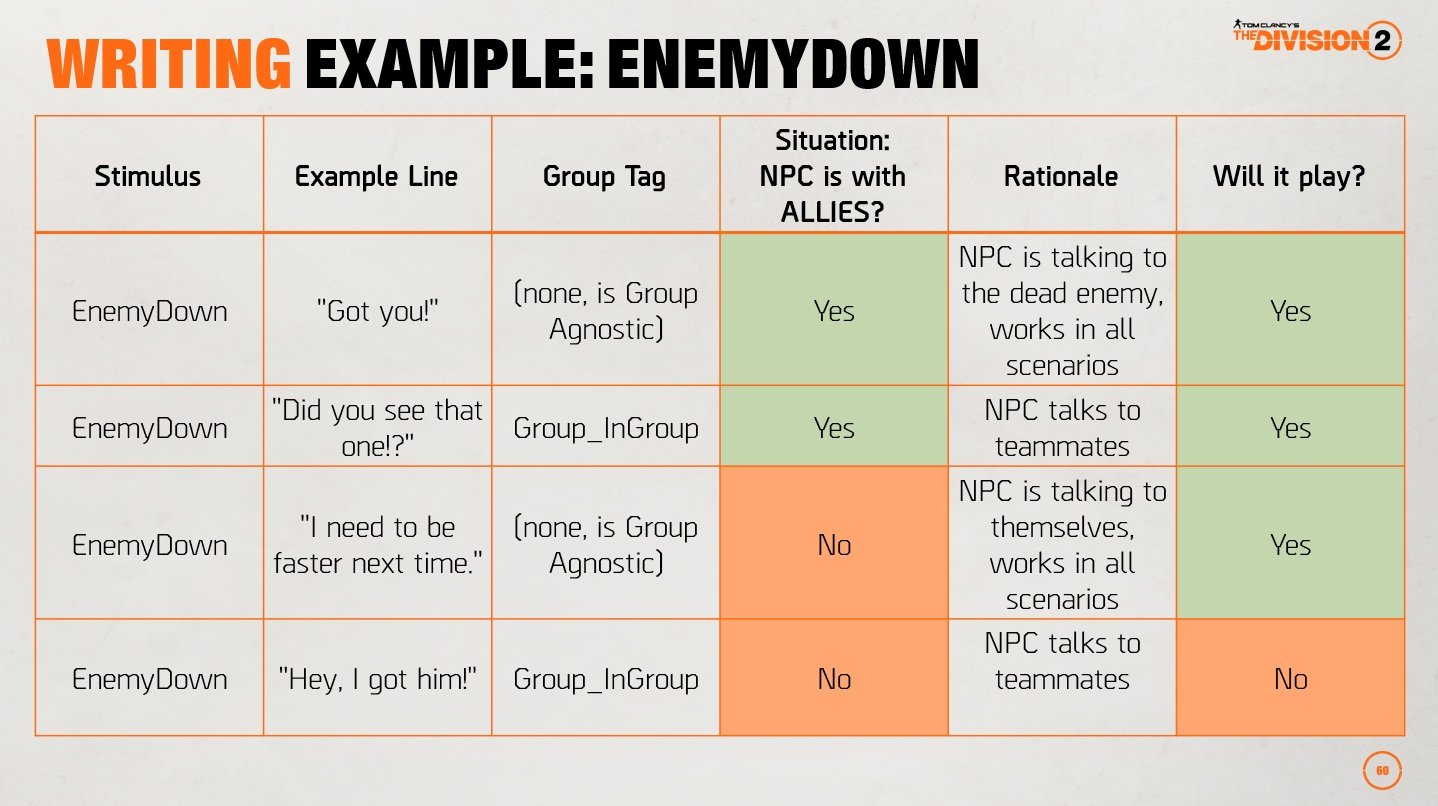

As with other areas of Audio Design, variation is important for managing audio fatigue and hiding repetition. For speech, this is not just how many variants a feature needs, but also what types of variation are needed. This includes contextual variation such as combat or stealth states, or who the character can speak to (themselves, an ally or a group); performed variants where we plan to use two or more slightly different performances of the same written line (there’s no perfect way to yell “reloading!” after all!); or how simple a line needs to be (longer and more colorful lines are fatiguing to hear repeated regularly).

We need to ensure that barks are natural things to say and that they are contextually accurate when they trigger

Where processing is concerned, there are the obvious needs for radio effects, robots, aliens, and the like; but mastering is also satisfying work. Managing the perceived loudness of projection levels (e.g. whether a line is whispered or yelled) is part of it, but there is also a world of creative opportunity here to carve out a unique sonic character for your project while making your life easier when mixing. What sounds great in isolation can often sound lackluster once in-game with reverb, propagation and the context of the broader soundscape.

The systems which support all of our various features are another area which require our attention and it is Voice Designers who are best placed to envisage this. Figuring out how to govern enormous numbers of assets efficiently, implement and mix our features as designed (while managing dialogue’s outrageous potential as a bug factory) are tasks that we cannot afford to leave to others.

Managing Complexity

Implementation is presentation. You can spend all the money in the world on fantastic performances, but it will sound absolutely terrible if it isn’t implemented with thought and care. Making a line play when something happens is easy enough to do, but it takes a lot more than simply importing assets to middleware. We need to ensure that the various assets are paced as deliberately as in film or TV shows, they must be contextually accurate and not result in spam. In a similar way to mixing for games, this sort of editorial at runtime requires a number of essential features:

- Scripted VO to play the files in a scene using the correct in-game characters with the desired pacing between each line

- Contextual Tags to ensure the content we play is contextually accurate

- Call & Response to allow barks to trigger new barks on other characters, with the desired pacing between them

- Cooldowns to prevent lines from spamming and control what plays and when (pacing again!)

- Dialogue Management to prevent characters speaking over themselves and control the overall flow of content (also pacing!)

Combine this with the need to drive subtitles, procedural facial animation as well as flags for UI or animation, and we inevitably leave audio middleware to head into the realms of proprietary systems in the game engine.

We also have scale to worry about; 100,000 assets in the Actor-Mixer Hierarchy would be impossible to manage effectively, but that’s where Wwise External Sources come to the rescue. Storing the assets outside of Wwise massively simplifies the hierarchy to a mere handful of objects and provides the flexibility to re-use content with different behavior, all without having to copy-paste those assets all over the place!

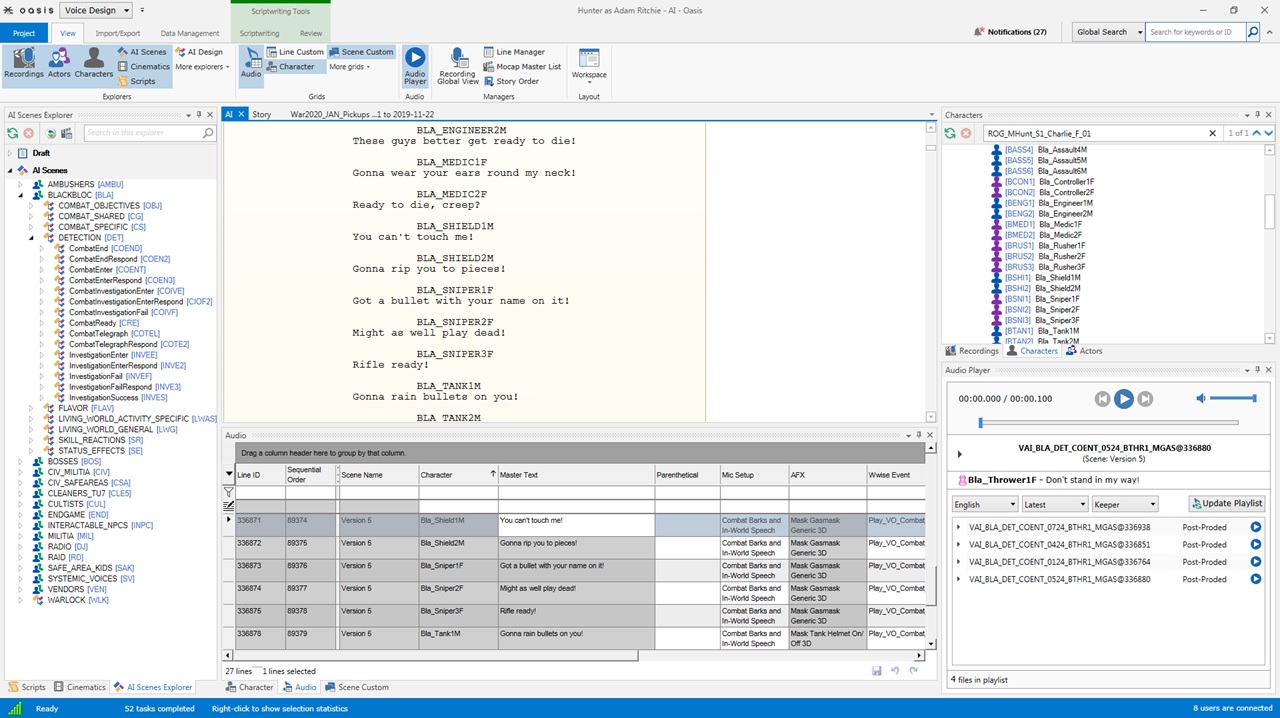

Text Databases provide a place for Voice Designers to design, organize and manage content and for writers to write that content. These come in all shapes and sizes; from glorified Excel spreadsheets with tons of VBA functionality, to full fledged proprietary applications or even online databases with browser interfaces. What they all have in common is that they produce metadata which the various dialogue systems can use to find the right asset and subtitle to play.

Ubisoft Technology Group’s Oasis text database

While we may spend a bit less time working in middleware than the average Audio Designer, Wwise remains an enormously powerful creative tool for us. Some things are still better achieved using regular sound objects such as vocalizations triggered by animations or walla systems. Furthermore, External Sources still allow us to use sequence and random containers to trigger dialogue driven SFX such as radio squelches.

At the point of pre-mixing or mixing, our experience with Wwise is much the same as any other audio discipline. We make full use of its functionality to create an exciting, atmospheric and engaging (and intelligible!) mix.

Striking the Right Tone

Just as style exists in Sound Design and Music, so it also exists in Voice Design. It can be cartoonish and fun, theatrical and melodramatic, or grounded and naturalistic. Finding the right balance on the gamey to cinematic spectrum is absolutely key. You couldn’t take vocalizations from Call of Duty and expect them to work in Borderlands. Both are gory, bloody franchises; but tonally, the two couldn’t be further apart.

This sense of style can be expressed across all aspects of Voice Design. It is often the accumulative effect of thousands of small decisions which comprise the project’s style and tone through voice. Battlefield I’s visceral adrenaline-fuelled combat experience is a good example, where it can be seen in casting, recording, direction, performance and mastering. Barks were recorded with literal physical effort and the mastering often cooking into the red. Working in concert with sound design and mix, this makes for a heady and atmospheric combat experience for the player; which would be completely undermined if delivered with the wooden gusto of isolated, stationary performers in the booth.

Battlefield 1 voice actors carry weight for German voice recordings

None of this can be achieved on a whim. Voice Design has to start in the earliest days of pre-production by specialist internal staff. Radical ideas for new features cannot be implemented mid-way through production as we need to understand their implications for the entire pipeline; from casting all the way through to the project’s tooling requirements.

A Growing Discipline

Though there are a little over 150 of us in the industry worldwide (by my count), in-house dialogue specialists are quickly becoming more commonplace. With several new positions opening every month, it is not unusual to see teams of three or more Voice Designers on a project these days; with Sony, EA, Ubisoft and others leading the way.

For anyone looking to make a transition into the games industry, it is well worth considering as a career path. Voice Design is an area of game audio which is as broad and deep as Sound Design or Music, fast-growing and still frontier country with enormous opportunities for discovery and innovation!

It is worth stating that you don’t need to know everything. There are Voice Designers that lean more toward design and tech, while others focus on other areas such as casting and production. Just as with Sound Design, it takes a broad palette of skills to handle the Voice Design for a project, and that’s what teams are for!

If you’re interested in learning more, a good place to start would be my good friend and colleague Adam Ritchie’s GDC talk on the Voice Design for The Division 2. It provides an excellent overview of the discipline.

NPC Voice Design in The Division 2

I am also collaborating with Leonard Paul on a Dialogue add-on for the School of Video Game Audio, with the intended aim of making the process of learning Voice Design more accessible. To hear updates on our progress, feel free to follow the school on Twitter or LinkedIn.

I’ve also set up a portal website: VoiceDesignResource.com. Here, I collate useful videos, articles and other resources which are often difficult to find.

Comments

Mark Estdale

January 28, 2023 at 04:10 am

Superb article Charlie Best in-depth overview I’ve seen.!